March 30, 2011 — As Remapping Debate recently reported, New Jersey’s fiscal problems have given rise to an intense debate between the state and its municipalities about the fairest and most effective way to close the state’s budget gap. But while local officials claim to be open to creative ways to deliver services more effectively, most stop short when it comes to one promising but politically difficult option: municipal consolidation.

For several decades, economists and good-government advocates (as well as some state officials) have pointed to New Jersey’s fragmented system of 566 municipal governments (in addition to separate school districts and county governments) as a key source of the state’s fiscal problems and high property taxes, and have identified millions of dollars in potential savings if the number of local governments were reduced. In addition to the fiscal benefits, there may be other advantages, including better service delivery and less economic segregation between towns.

But several efforts over the years by the state to encourage the consolidation of small municipalities have failed to produce significant results, and only one consolidation has taken place in the last 50 years.

In 2007, consolidation advocates were given new hope. The state legislature created the Local Unit Alignment, Reorganization and Consolidation Commission to facilitate consolidations while shielding state and local officials from the political fallout those officials fear might occur, even when such consolidations would serve the interests of both local residents and the state as a whole.

LUARCC was charged with studying and reporting on the ways that municipal governments could operate more efficiently, and on the ways that the state government could facilitate the process of consolidation and shared services. Most notably, LUARCC was given the authority to recommend specific consolidations, proposals that residents would have to vote up or down.

Four years later, many of LUARCC’s responsibilities have not been fulfilled, and potential municipal consolidations remain stalled. The reason, commission members say, is lack of funding. Despite Gov. Christie’s professed support for consolidation, even for his own hometown, his 2010 budget completely defunded the commission, and no funds have been restored this year.

Given the substantial and permanent cost-savings that could result from numerous consolidations, and the fact that LUARCC’s funding comprised only a tiny portion of New Jersey’s overall budget, questions have been raised about the wisdom of not allowing LUARCC the opportunity to see if its mechanisms could have overcome local resistance to change. And, some advocates say, the decision to defund LUARCC obscures municipal consolidation as a viable alternative to a locality that is currently choosing between reducing services or raising property taxes beyond a state-imposed cap.

A complicated process in a highly fragmented state

Though several states, including New York, Pennsylvania, and Iowa, are wrestling with the issue of municipal fragmentation, New Jersey has received the most attention because of its vast number of jurisdictions, and the direct link, made by many, to the state’s high property taxes.

New Jersey has more municipalities — both per-person and per-square-mile — than any other state in the country. There are more local governments for New Jersey’s 8.8 million residents than for California’s 37.3 million. There are several historical reasons for this fragmentation dating back to the founding of the colony: some municipalities, for example, split off from larger towns to avoid the prohibition of liquor sales there; others were formed in order to facilitate the exclusion of African-Americans.

According to Gina Genovese, executive director of Courage to Connect New Jersey, a recently formed non-profit group that attempts to educate the public about the benefits of consolidation, “efficiency was clearly not on people’s minds when these governments were formed.”

“It’s widely agreed,” said Genovese, who is also the former mayor of Long Hill Township (pop. 8,702), “that New Jersey could save a significant amount of money if we consolidated towns on a large scale. And more than money, we could be delivering better services.”

Though there are no precise estimates on how much money the state as a whole could save through large-scale municipal consolidate, Genovese said that it could easily be hundreds of millions of dollars a year.

The problems of fragmentation stem, in part, from the fact that many of the towns in New Jersey don’t have sufficient population to generate a robust tax base. Additionally, larger towns often benefit from economies of scale — the increase in efficiency in the production of goods or the delivery of services when the volume of goods or services increases. Finally, Genovese said, fragmentation breeds redundancy: “Do we really need five mayors to govern twenty square miles? Do we need five police chiefs?”

New Jersey state law does provide an avenue for towns that wish to consolidate, but in practice, this process is fraught with complications and delays.

The Borough of Merchantville and the adjacent Township of Cherry Hill, for example, applied for a study commission on consolidation, but the application was denied by the Local Finance Board because one town had approved it through direct petitioning of residents while the other approved it through the Town Council. (New Jersey’s Legislature voted unanimously to change the law this month in order to rectify this apparently unintentional effect, and the measure awaits the Governor’s signature.)

On at least one occasion, towns that have asked for funding were told that the Department of Community Affairs didn’t have the money.

And local voter resistance remains strong.

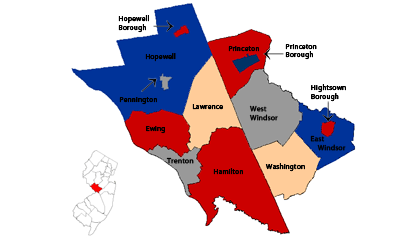

For example, Princeton Borough is actually completely surrounded by Princeton Township — in local parlance, the Borough is a “donut hole” town — leading many to question why there are two separate governments, especially as property taxes have risen in both.

The residents of the jurisdictions have considered consolidation three times before, and each time they have voted it down, according to State Assemblyman Reed Gusciora, who represents the district that includes the Princetons. “People are afraid of change,” he said. “They want to hold on to their little fiefdoms.”

A fourth referendum is scheduled to be held this fall.

Municipalities won’t do it on their own

According to Jon Shure, Deputy Director of the State Fiscal Project at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a national think-tank, there are so many obstacles to consolidation that it’s not surprising that more municipalities haven’t taken steps in that direction.

“There are clearly too many towns and too many school districts in New Jersey,” he said, “but people can’t seem to think in a larger area than four square miles. If it’s ever going to be resolved, it has to be resolved by imposing it from the state level.”

In fact, there have been several past attempts by the state to create stronger incentives to push municipal consolidation, but none of them were successful.

“People just didn’t want to,” said State Senator Robert Gordon. “There are political costs to merging your fire departments or police department. People thought the costs were just too high.”

A federal model

The LUARC Commission was modeled on a federal program, the Defense Base Closure and Realignment (BRAC) Commission, which was instituted in 1989 to close unnecessary military basis. Prior to BRAC, Congress had found it very difficult to close military bases, even when they were no longer useful, because a military base can bring millions of dollars to a district, and politicians that represented such districts often objected.

BRAC circumvented these challenges by creating a list of bases that should be closed and then providing that list to Congress. Congress then had to vote “up or down” — meaning it had to approve the entire list or none of it — which made it easier for individual politicians to close bases in their own districts. To date, the BRAC process has resulted in the closure of nearly 100 bases.

“LUARCC was the same idea,” said Andrew Bruck, research director for Courage to Connect. “Since there are a lot of vested interests in each municipality, you need to insulate politicians from the process.”

LUARCC’s charter (which specifically mentions BRAC as inspiration), empowers the Commission to “study and report on the structure and functions of county and municipal government….and the appropriate allocation of service delivery responsibilities from the standpoint of efficiency.” It is also required to recommend legislative changes at the state level to encourage shared services and consolidation, and then to identify specific municipalities that could benefit from sharing services or consolidating.

LUARCC would then conduct or hire outside contractors to conduct feasibility studies that would demonstrate the particulars of how consolidation would work in specific circumstances, write a detailed consolidation proposal, and submit the proposal to the state legislature. After approval by the state, the proposal would go directly to residents for an up or down vote, a process that eliminates the initial hurdle of requiring local approval even before a study can be conducted.

In the original legislation, proposed by State Senator Joseph Kyrillos, LUARCC would have produced a list of municipalities to consolidate, and then the legislature would vote up or down on its recommendations, exactly like the BRAC Commission. Before the bill was brought to a vote, however, rival legislators modified it by adding a provision that required voter approval of any consolidation plans. The revised bill passed by a large majority. Even if LUARCC’s funding were restored, the added provision, some say, might prove to be a serious impediment to LUARCC’s effectiveness.

Nevertheless, according to State Assemblywoman Pamela Lampitt, LUARCC could play a valuable role in encouraging municipalities to consolidate, effectively changing the dynamic between the state and local governments by singling out municipalities that should consolidate, and then performing the so-called “feasibility studies” for them.

“The problem is that somebody’s got to be the bad guy here,” she said. “Everybody loves their local mayor. So, here’s the bad guy. The challenge will be to make residents understand that [consolidation] can be a seamless process for them.”

That would require giving LUARCC the funding and the staffing to do feasibility studies so that residents and local officials would see concretely the cost-savings that would result from consolidation, Bruck said. By performing the studies itself, LUARCC would also save the localities the expense normally associated with consolidation studies.

Additionally, Bruck said, LUARCC would make consolidation a more visible alternative for towns now focused on whether to raise property taxes or cut services (and eliminate an excuse for not exploring consolidation as an option).

During its first two years of operation, the Commission produced several reports and literature reviews on municipal size, efficiency, and tax rates, discharging the first stage of its responsibilities under its charter. The next step, according to Commission Chair John Fisher, was to perform feasibility studies with respect to specific municipalities that appear to be good candidates for consolidation, studies which would then lead to the submission of formal consolidation proposals to the state for approval.

“That was the threshold we got to when funding got cut,” Fisher said.

The commission has still been meeting at least once a month, Fisher added, but it no longer has the means to perform or contract for feasibility studies in order to test its preliminary hypotheses with data and analysis.

Defunding LUARCC

According to Kevin Roberts, a spokesperson for Gov. Christie, “[t]he decision to defund LUARCC was due to the unprecedented fiscal crisis faced by the state in the last fiscal year, a policy we’ve continued in the proposed [fiscal year 2012] budget.”

LUARCC’s precise budget in 2009 was not immediately available from the Department of Community Affairs. Fisher said, however, that LUARCC had received only $500,000 in 2009 for “consultancy costs”; additional costs included the salary of an Executive Director and some materials and office supplies, but Fisher said that total was not more than $1 million. In relation to Gov. Christie’s proposed budget for 2011-2012, which included $29.4 billion in total expenditures, $1 million would be equivalent to 0.0034% of the total. Even if LUARCC were significantly expanded (Fisher declined to provide cost estimates for an expansion that would include additional duties), the savings that could result from the consolidation of even a small number of towns could easily offset the cost of the commission, said Bruck. Roberts did not respond to a follow-up question about the range of cost efficiencies the Governor believes could result from consolidation on a large scale.

In an email message, Roberts said that along with raising property taxes or cutting services, consolidation is a “third option” for municipalities to balance their budgets, and that part of the justification of the Governor’s two-percent cap on property taxes was to “force some of these decisions concerning municipal consolidation and/or shared services” in a manner he described as being “from the bottom up.” But Roberts did not respond to a question asking whether it was Christie’s view that municipalities should look first to potential efficiencies that could be achieved via consolidations before either raising property taxes beyond the cap or cutting services.

And, according to Chuck Chiarello, Mayor of Buena Vista Township and current president of the League of Municipalities, the effect of defunding the commission is that, relative to increasing property taxes or cutting services, consolidation has become a less visible alternative to small municipalities.

Roberts cited the “tool-kit” being promoted by Christie — including arbitration caps and changes to civil service law designed to reduce municipal labor costs — as another alternative to raising taxes or cutting services.

Roberts did not explain, however, why promoting the tool-kit and empowering LUARCC were mutually exclusive goals, and likewise did not explain why, in the context of facing the stick of tax increases or service cuts, a funded and functional LUARCC process wouldn’t appeal to beleaguered municipalities as a welcome carrot.

In any case, the tool-kit might be beside the point, according to Genovese: “Those [tool-kit] reforms might save municipalities some money,” Genovese acknowledged, “but if at the end of it, you still have this system, it’s still not going to hold up in the long-term. You’re still just feeding into this incredibly inefficient system.”

The future of LUARCC

Andrew Bruck characterized LUARCC as a short-term investment that could lead to significant long-term savings and, given that reality, he said that the decision to defund the commission was shortsighted. Roberts did not respond to a follow-up question regarding the argument that the potential benefits that could be yielded from funding LUARCC would do more for the fiscal health of the state than the amount saved by cutting LUARCC’s funding.

“We really need to consolidate our consolidation policies,” Bruck said. “LUARCC is a great way to start that process. Let’s start with what we already have.”

LUARCC Chairman Fisher made the same point: “We have an entity that was the result of a thoughtful legislature. Let us be the focal point and be responsible for starting this process.”

Roberts did not respond to a follow-up question asking when, if at all, Gov. Christie plans to restore LUARCC’s funding.

Jon Shure at the Center on Budget and Policies Priorities cautioned that bringing LUARCC back to life would not necessarily be a cure-all, noting that experience has shown that a “carrot-only” approach has not been effective. The case of the Princetons exemplifies how residents can resist consolidation even when the cost-savings are clear.

That resistance has led some to conclude that stronger medicine is needed.

Such an approach was actually proposed a few years ago by then-Governor Jon Corzine.

In his 2008 budget, Corzine proposed to drastically cut state property tax relief aid to municipalities with fewer than 10,000 residents. In that proposal, towns with between 5,000 and 10,000 residents would have received half of their usual allotment of state aid, and towns with fewer than 5,000 residents would have received no aid at all. At the same time, Corzine would have offered $32 million in grants to help towns that did consolidate.

That proposal did not make it into the final budget, according to Bruck, largely because the New Jersey State League of Municipalities lobbied so hard against it.

William Dressel, executive director of the League, confirmed that he had opposed the provision, and added that he would oppose any bill that “penalized municipalities for voting against consolidation.” Several local officials echoed that sentiment.

Dressel explained his opposition in terms of the state’s alleged failure to offer “carrots,” but, like Shure, some state lawmakers, say the approach of just offering carrots has been tried and found wanting: incentives that were offered in the past were not used by many municipalities, and failed to achieve significant results.

Latest proposal

New Jersey State Senate President Stephen Sweeney does think that sticks need to go with carrots. He has recently proposed a bill that, in addition to refunding LUARCC, would deny the amount of state aid that LUARCC determined might have been saved through a shared-service agreement to a town that subsequently voted it down.

Bruck said that this principle could also be applied to consolidation recommendations.

But Bruck said that even that stick might not be big enough. The proposal that he advocates would put all the state aid to municipalities with populations under 10,000 in escrow. “If they agreed to do a consolidation study, they would get half of it back,” he said. “If they actually consolidated, they would get two or three times the amount of aid back.”

That would have the effect of motivating towns to consolidate quickly to compete for the aid in the fund. “Right now there’s no momentum,” Bruck said. “We have to incentivize towns to go first.”

Bruck acknowledged that that proposal is unlikely to gain the support of the state legislature, not to mention the towns themselves, at least in the immediate future.

In the near-term, however, many agree that it does not make sense to have LUARCC sidelined when potential benefits of consolidation are so much larger than the costs of running the Commission.

“The first step,” Bruck said, “is to reinvigorate it.”