June 18, 2025 — New York’s incentive-based “Pro-Housing Community” program, designed to spur development where it had long languished behind the barriers of rigid zoning restrictions (“exclusionary zoning”) is, a little short of two years after commencement, not doing that. A large percentage of municipalities in Westchester and Nassau Counties — two of the beating hearts of exclusionary zoning in the New York City metropolitan area — are saying in effect, “No, thank you, we like our exclusion just the way we have it.” The lack of progress is especially apparent in municipalities with the lowest percentages of non-Hispanic Black residents.

Hochul’s initial plan: carrots and sticks

Once upon a time (in was in January 2023), New York Governor Kathy Hochul announced a new program to help deal with what she called an “historic housing shortage.” By New York standards, the program, dubbed the “New York Housing Compact,” was radical: here was a plan that required less restrictive zoning within a half-mile of every MTA rail transit stop, and a remedy to allow (within limits) as-of-right development in those locations if municipalities did not comply; a plan that set a 3 percent growth target for downstate municipalities each three years (with safe harbors and other wiggle room), but with a new mechanism to fast-track projects with an affordable housing component (with appeals from local denials handled either by a newly created state-level Housing Appeals Board or through the courts).

This compared to New York State’s decades-long record of doing nothing legislatively or through gubernatorial action to address exclusionary zoning. [Disclosure: Wearing my hat as a civil rights advocate in 2023, I supported the Housing Compact and urged that its provisions be made stronger.]

The Governor’s plan did not fare well.

It faced loud bipartisan opposition from many suburban legislators, but received only muted support from state legislators based in New York City for whom a more balanced regional approach to development would have helped ease the intensity of the housing crisis their constituents were living through (see sidebar on the regional dimension to New York City’s housing crisis).

State legislative leaders (Carl Heastie in the Assembly and Andrea Stewart-Cousins in the Senate) were unwilling to spend political capital on the Housing Compact or any program that involved mandates.

The Housing Compact went down in flames by the end of Albany’s foreshortened legislative calendar (New York’s state legislative normally meets each year for a session a little shy of six months.)

Hochul’s replacement plan: carrots only

The Governor was acutely aware of the limitations of the carrots-only approach. In April 2023, in the course of acknowledging the Legislature’s resistance, she said, “[I]t remains clear that merely providing incentives will not make the meaningful change that New Yorkers deserve.”

Even when she announced her new, voluntary program in July 2023, Hochul recognized that it was her original Housing Compact (with mandates) – the one that the Legislature was not ready for and to which it would not commit — that was “the transformative change that New Yorkers so desperately need and deserve.”

The idea behind the new approach was to try to persuade municipalities to become less anti-growth. The mechanism? Only a municipality that became a “pro-housing community” would be able to apply for any of a group of state discretionary spending programs. Two paths to certification as a pro-housing community were made available: demonstrated growth or aspirational resolution. Downstate, a municipality would need to demonstrate approval of permits increasing housing stock by 1 percent over the previous year or 3 percent over the previous three years.

But, as noted, actual progress was not the only way to become certified. Municipalities could simply enact a model resolution, enacting a “pledge” to take “positive steps to alleviate the housing crisis,” modified later in the same sentence to “endeavor” to take a series of steps.

Those steps, if taken, could indeed make material change:

- Streamlining permitting for multifamily housing, affordable housing, accessible housing, accessory dwelling units, and supportive housing.

- Adopting policies that affirmatively further fair housing.

- Incorporating regional housing needs into planning decisions.

- Increasing development capacity for residential uses.

- Enacting policies that encourage a broad range of housing development, including multifamily housing, affordable housing, accessible housing, accessory dwelling units, and supportive housing.

Yet even in the frequently asked questions that the State’s Department of Homes and Community Renewal (HCR) – the agency overseeing the program – included, municipalities were told that, even though they were not permitted to change the text of the model resolution, that should understand that the resolution “is a statement of values, not a commitment to execute every option listed within the resolution.”1

According to Alex Armlovich, a Senior Housing Policy Analyst at the Niskanen Center, a think tank that describes itself as advocating “for a government that provides social insurance and essential public goods, fosters market competition and innovation, invests in state capacity, and does not impede productive enterprise,” the FAQ answer indicates that the program is designed to be more symbolic than substantively meaningful. It is “more like the 1980s version of California reform when they started with the Housing Accountability Act, but everyone kind of understood it to be symbolic rather than actual accountability,” he said.

- 1.

See page 2 of the document, question 1 of the “Applying to the Program” section.

A stark racial divide

Both counties (Nassau even more than Westchester) were hotbeds of opposition to the Housing Compact. Remapping Debate took advantage of the “Pro-Housing Communities Dashboard” made available online by HCR to see if any patterns could be discerned in how and where there had been “Pro-Housing Community” buy-in.

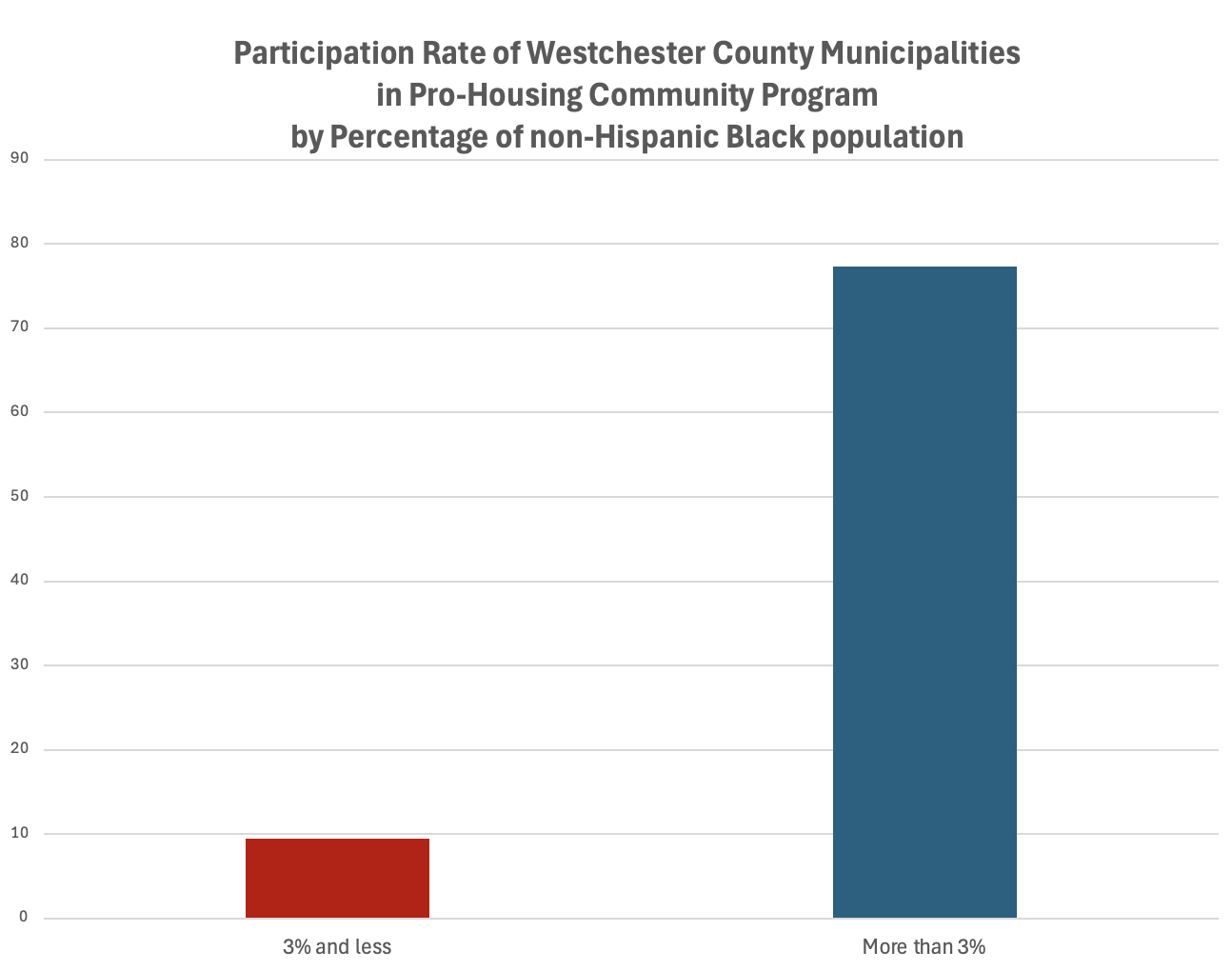

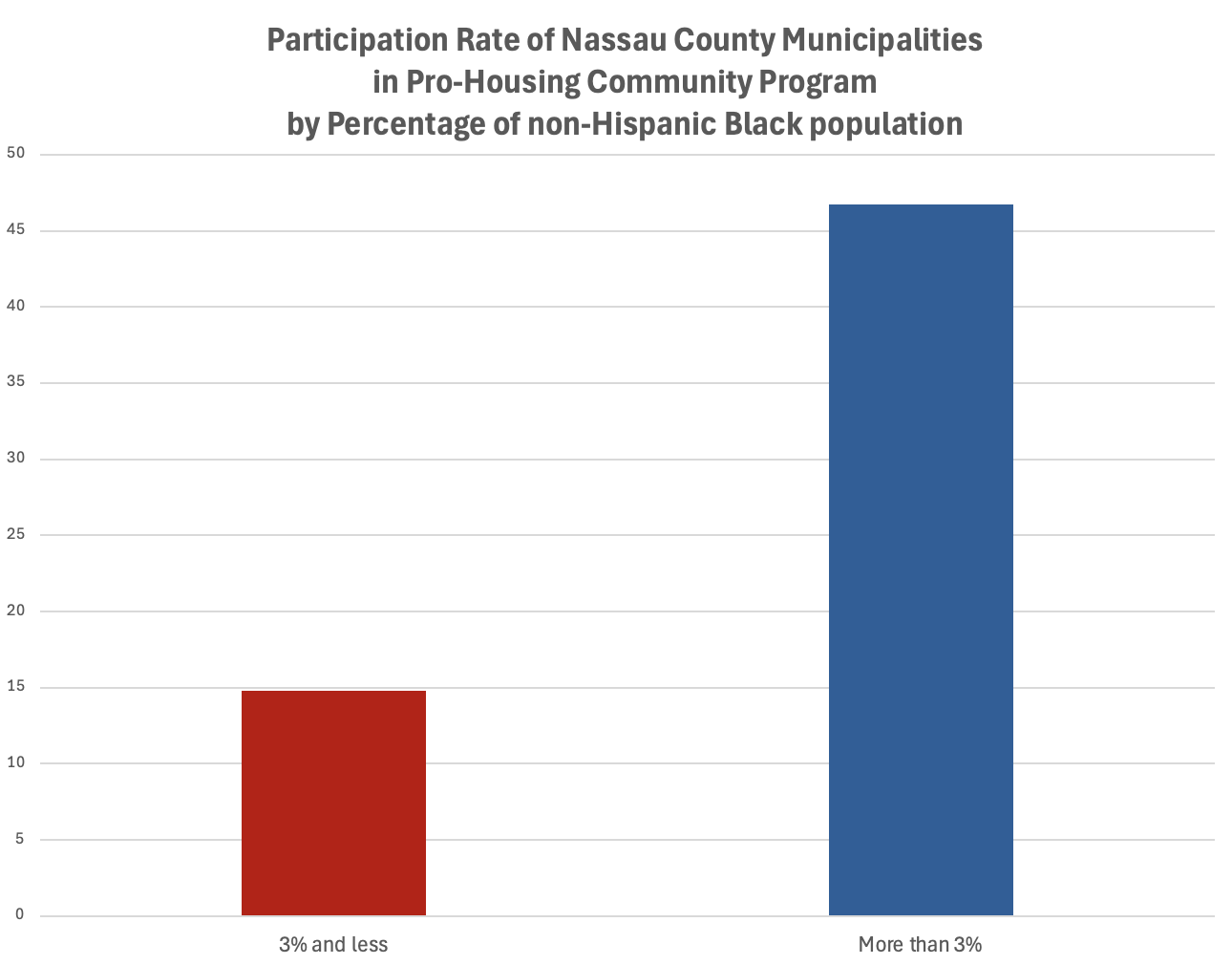

Overall, per 2020 Census data, non-Hispanic Black residents make up about 13 percent of Westchester’s population, a little less than 11 percent of Nassau’s population, and about 20 percent of New York City’s population. Our analysis broke out municipalities with a far lower non-Hispanic Black population – 3 percent or less – from other municipalities.

Westchester has a total of 44 municipalities (cities, towns, and villages); Nassau has 69. In both counties, a dramatically lower percentage of the 3-percent-or-less municipalities are participating in the pro-housing community program than is the case with more-than-3-percent municipalities.

In Westchester, of the 22 municipalities that have non-Hispanic Black population of 3 percent or less, only 2 have participated (either through a letter of intent or by one of the methods of certification). That is only 9.1 percent. One of the two (Sleepy Hollow) has a Hispanic population of 55 percent.

Of the 22 municipalities that have non-Hispanic Black population of greater than 3 percent, 17 are participating (of which 7 have combined Black and Hispanic populations ranging from 44 to 79 percent). That is fully 77.3 percent of the municipalities with greater than 3 percent non-Hispanic Black population.

In Nassau, 54 of 69 municipalities that have non-Hispanic Black population of 3.0 percent or less. (That is not a typo.) Of those, only eight are participating, a mere 14.8 percent. Six of the seven have thus far only provided a letter of intent (that is, they have not been certified). Two of the eight (Island Park and Manorhaven) have Hispanic population of 33.4 and 35.8 percent, respectively.

Of the 15 municipalities that have non-Hispanic Black population of more than 3.0 percent, 7 are participating; that is 46.7 percent. All are certified communities. Five have combined Black and Hispanic population ranging from 40.0 to 89.0 percent.

Overall, 43.2 percent of Westchester municipalities are participating; only 21.7 percent of Nassau municipalities are participating.

When is a carrot not a carrot?

Moses Gates of the Regional Plan Association said in an interview with Remapping Debate both that he was a “firm believer that you need both carrots and sticks,” but that he wanted to give more time to see how the Pro-Housing Community program played out. Nevertheless, he said that the kind of results being seen in Westchester and Nassau are “always the issue with the voluntary system that relies on funding.” He explained:

Places that don’t need funding are less likely to opt into the voluntary system… . If you don’t have some kind of enforcement mechanism, then this is what happens. The places that opt in are the poor places that need funding. And you’ve seen this with who’s opted into the Pro-Housing Community, not just in Nassau County, but across the state. You can see it and it is disproportionately the poor municipalities and, honestly, the municipalities with less of a housing crunch for the most part — a lot of places upstate that have opted in. And some of the places that are the most expensive, largely have not. And this is the weakness of only having a voluntary system.

The Niskanen Center’s Armlovich took the Westchester and Nassau results to date as being “suggestive that the supply problem is the bulk of the [affirmatively furthering fair housing] problem … I don’t think you can deny that the bulk of the unfairness in our housing market is driven by growth control with malintent.”

Turning to the problem of tailoring an effective system, Armlovich said that, “[I]n order for to be a carrot, it has to be something you care about, and, likewise, for it to be a stick, it has to be something you’d fear, and different jurisdictions have different views of that.” He added, “You have to think very carefully about, “Is this a set of funds that is viewed as a carrot by the jurisdiction in question?’”

The question seems pertinent given the nature of the discretionary funding involved. It seems unlikely that many municipalities that have devoted themselves to pursuing an anti-growth agenda would be interested in such funding.1 For example, will a small village in Nassau County be interested in a “large-scale, transformative project that will have lasting impacts on Long Island”? Would a town in Westchester County delighted with its inaccessibility want funding to “upgrade and enhance public transportation services? How many municipalities with exclusionary zoning in place will be interested in funding to help their downtowns (if they exist) become “magnets for redevelopment, business, job creation, and economic and housing diversity”? Perhaps the Hochul administration has a rebuttal to the answers “no” and “few, if any,” but, as noted above, chose not to discuss the program.

- 1.

The full slate of funding streams for which a Pro-Housing Community can receive preference over those municipalities that have are not participating in the program consists of the following:

The Downtown Revitalization Initiative“transforms downtown neighborhoods into vibrant centers that offer a high quality of life and are magnets for redevelopment, business, job creation, and economic and housing diversity.”

The New York Forward program is intended “to invigorate and enliven downtowns in New York’s smaller and rural communities—the type of downtowns found in villages, hamlets and other small, neighborhood-scale municipal centers.”

The Regional Council Capital Fund Program provides funding “for capital-based economic development initiatives intended to create or retain jobs; prevent, reduce or eliminate unemployment and underemployment; and/or increase business activity in a community or region.”

Market New York is “a grant program established to strengthen tourism and attract visitors to New York State by promoting destinations, attractions and special events.”

New York Main Street “provides financial resources and technical assistance to communities to strengthen the economic vitality of the State’s traditional Main Streets and neighborhoods.”

The Long Island Investment Fund program “will focus on large-scale, transformative projects that will have lasting impacts on Long Island.”

The Mid-Hudson Momentum Fundprogram “invests in mixed-use housing and infrastructure projects throughout the Mid-Hudson Region to address the recent population increase to the area.”

The Public Transportation Modernization and Enhancement Program provides funding to “upgrade and enhance public transportation services.”