Jan. 11, 2012 — As Remapping Debate recently reported, the short-term fiscal crisis facing the City of Detroit is actually a reflection of more long-standing structural problems related to a shrinking population and an eroding tax base. While it is tempting to see these problems as generated by the city alone, the afflictions facing Detroit are rooted in the way that the region as a whole was allowed and encouraged to develop over the last several decades (see “From boom to bust,” below).

For this reason, many experts believe that any solution to Detroit’s structural problems will require a strong regional component. “Detroit simply does not have the tools necessary to address this problem on its own,” said Dan Gilmartin, executive director of the Michigan Municipal League. “The region is much too fragmented and divided, and there are too many obstacles to growth. Any holistic solution has to address the suburbs as well as Detroit.”

All of the short-term proposals currently offered by city and state officials fail to do this. There was a time, though, when policy makers and advocates were considering broader approaches. In the late 1960s and 1970s, when Detroit’s problems were becoming more and more apparent, several regional solutions were proposed. Had they been put in place at that time, experts say, those solutions could have substantially mitigated Detroit’s decline and may even have prevented it.

Largely due to long-standing antipathy between the city and its suburbs, however, all of these opportunities were squandered. The result: the Detroit metropolitan area has remained one of the most polarized, fragmented, and segregated regions in the country, and many of the drivers of Detroit’s decline continue unabated.

The Option Process and the Local Cooperation Act

As the City of Detroit shrank and the Detroit metro area grew rapidly in the 1960s and 1970s, it became apparent that there was no effective planning happening at the regional level and little coordination between the municipalities.

“You had all these little towns competing with each other and with the city,” said John Mogk, a professor of law and an expert in urban planning at Wayne State University in Detroit. “Everybody was worrying about themselves without thinking about how their decisions would affect the region as a whole.”

In the mid-1970s, two significant proposals attempted to remedy the situation. In 1972, the federal government commissioned a local committee to study the problems facing the region and report back with suggested solutions. This commission was called The Option Process (TOP) Task Force, and included officials from various levels of government, as well as representatives from business and labor. Mogk served as the chairman.

In its final report,published in early 1973, the Task Force made a number of recommendations to then-Governor William Milliken, including several proposed revisions to state and federal law. The changes focused on the allocation of housing, transportation, health, and education funding.

In addition, the Task Force recommended that the power of the Southeast Michigan Council of Governments (SEMCOG) — then, as now, a voluntary membership organization with a limited role — be greatly increased and that its system of representation, which favored the suburbs over Detroit, be changed.

It also recommended the creation of several new authorities to plan for and coordinate in regards to economic development, health care delivery, transportation, and housing, all to be housed under the new regional agency.

“It was very ambitious,” Mogk said. “We wanted to give an honest assessment of what the problems were and what it would take to solve them.”

The Task Force made its recommendations while Roman Gribbs was the Mayor of Detroit. According to Mogk, Gribbs was very interested in the report’s findings. In 1974, however, Coleman Young was elected, and he showed far less enthusiasm. “Young never displayed any interest in this at all,” Mogk said. Without support from either the city or the suburbs, none of the report’s recommendations were put into place.

While local apathy was mirrored, for the most part, in the State Capitol, there were a handful of state officials who displayed an interest in regionalism at the time, including Governor William Milliken and Speaker of the State House of Representatives William Ryan. In late 1975, Ryan introduced a bill to the legislature called the Local Cooperation Act, which also would have created a new regional planning agency to replace SEMCOG. As with the TOP report, the bill went nowhere.

“There’s never been any kind of long-term plan”

Under both proposals, a new regional entity would have been charged with creating a long-term master plan for the region. Especially in terms of land use and economic development, Mogk said, this could have had substantial benefits.

“Most of the new factories that were built in the area after World War II were built in the suburbs,” Mogk said. Advancements in technology required factories to be single-story, which made many of the multi-story factories in Detroit obsolete. In the suburbs, there was a significant amount of cleared land available to be bought cheaply. According to Mogk, there was still a sizable amount of available land in Detroit, as well, but building on it would have required rezoning and, in some cases, moving residents from one part of the city to another. That relocation would likely have required the construction of new, affordable housing.

Had an entity existed with the resources and authority to create a regional master plan for land use, Mogk said, it may have been possible to arrest the process of deindustrialization in the city. “If you had an economic and land use plan, you could have said that a certain number of acres would be dedicated to industrial use, a certain number for affordable housing, a certain number for commercial use, and you could have made decisions about where in the region those investments should be made.”

Joe Darden, an assistant professor of geography at Michigan State University and a co-author of Detroit, Race, and Uneven Development, agreed. According to Darden, it would have been especially beneficial if housing and transportation policy had been made on a regional basis, as the Task Force had recommended. Placing more affordable housing in suburban communities would have made the region less segregated and potentially reduced the white flight from the city, he said, and coordinating transportation regionally would have allowed for more mobility for city residents to jobs in the suburbs, and vice versa.

Darden also pointed out that the lack of coordination in the region has led to significant duplication of services. “Everybody wants to have their own fire department, their own school system, their own sanitation department,” he said. “That’s a tremendous waste of resources that could be used for productive purposes.”

Both Mogk and Darden said that the region would look very different today if the Task Force recommendations had been put into place or the Local Cooperation Act passed. “There would probably be much more balance in terms of investment between Detroit and the suburbs,” Darden said. “The movement out of the city would not have been as great, and Detroit would have gained from an economic standpoint.”

Milliken v. Bradley

The Detroit region has long been one of the most segregated metropolitan areas in the country. By 1970, African Americans had already become largely concentrated in the city, while the suburbs were almost exclusively white.

Because African Americans were locked out of many of the new, well-paying jobs in the suburbs, and because the city was not producing many jobs of its own, Detroit became steadily more impoverished throughout the 1960s and 1970s. “When you have vastly unequal places in a region, investment goes to the richer one,” Darden said. “So some of Detroit’s suburbs are some of the wealthiest towns in the country, and in Detroit you have an astounding level of concentrated poverty.”

During this period, there was significant segregation within the city itself, Sugrue said, with some neighborhoods being entirely white and others entirely black. “The city failed numerous times to build affordable housing in white neighborhoods,” he said. “There was extremely strong neighborhood resistance to that.”

Recognizing that segregation was also extremely prevalent in Detroit’s school system, and that largely black schools performed much more poorly than largely white schools, the Detroit Board of Education passed an order in 1970 that would have bused white children to black schools, and vice-versa. A locally based recall campaign followed, and the state passed a law that voided the plan and kept school districts under neighborhood control.

Later that year, the NAACP sued the state and the school board in federal District Court, arguing that, as in Brown v. Board of Education, separate was not equal, and that the policies of the state and school board had deliberately kept the school system segregated. The case was entitled Milliken v. Bradley.

The district court found in favor of the NAACP and ordered the school district to draft a desegregation plan. The city presented the court with three different Detroit-wide plans, all of which the court rejected. The court then ruled that it was not possible to desegregate the Detroit Public School System without including the suburban communities. The city was ordered to submit a “metropolitan” plan that would eventually encompass a total of fifty-four separate school districts, busing Detroit children to suburban schools and suburban children into Detroit.

On appeal, however, the Supreme Court ruled against the NAACP. Even though the organization had presented evidence of housing segregation that operated on a metropolitan level, Chief Justice William Burger claimed that “the case does not present any question concerning possible state housing violations,” and Justice Potter Stewart, who cast the key fifth vote dooming a metropolitan remedy, asserted that housing segregation was caused by “unknown and unknowable causes.”

The impact of the case was enormous. According to Gary Orfield and Susan E. Eaton in their 1996 book Dismantling Desegregation, “By failing to examine housing, the Court gave neighborhoods that had successfully segregated their housing an exemption from school desegregation requirements. City neighborhoods that had not excluded, blacks, on the other hand, faced mandatory desegregation.” The court effectively blessed suburbs with all-white schools as “refuges for whites fearful of minorities moving into their schools,” Orfield and Eaton wrote.

More generally, according to Dismantling Desegregation, the “Supreme Court’s failure to examine the housing underpinnings of metropolitan segregation” in Milliken made desegregation “almost impossible” in northern metropolitan areas. “Suburbs were protected from desegregation by the courts ignoring the origin of their racially segregated housing patterns.”

A “hopeless” problem?

“Milliken was perhaps the greatest missed opportunity of that period,” said Myron Orfield, professor of law and director of the Institute on Race and Poverty at the University of Minnesota (the brother of UCLA’s Gary Orfield). “Had that gone the other way, it would have opened the door to fixing nearly all of Detroit’s current problems.”

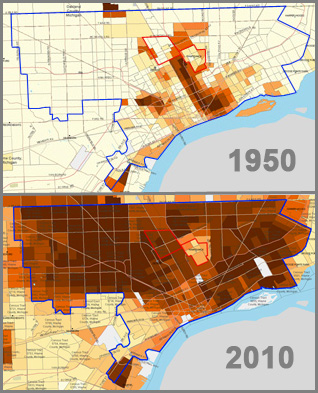

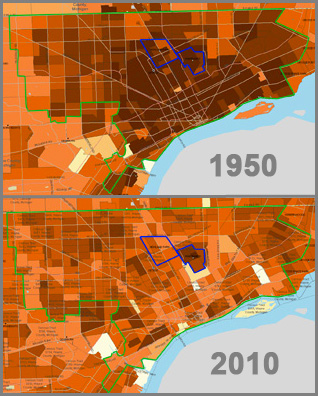

Orfield said that had the region’s school districts been successfully desegregated, it would also have put pressure on officials to open up housing opportunities to African American families in the suburbs. “Housing segregation and school segregation are intimately linked,” he said. “Where you have one you always have the other.” (See maps of segregation in Detroit over time.)

It is also likely, had the metropolitan remedy gone into effect, that the white flight out of the city would have been much less severe, according to Mogk. Mogk served briefly on the school board at the time, and he urged the NAACP to include the suburbs in its initial complaint, which the NAACP declined to do. When the suburbs were ultimately insulated from the remedy, the busing plan only took effect inside the city lines, making it possible for white families to avoid sending their children to largely black schools simply by moving to a nearby suburb.

“Everybody thinks that it was the riots [in 1967] that caused the white families to leave,” he said. “Some people were leaving at that time but, really, it was after Milliken that you saw mass flight to the suburbs.”

Mogk said that if the case had gone the other way, it is likely that Detroit would not have experienced the steep decline in its tax base that has occurred since then.

“When you have big areas that are largely poor, that’s the last place that new businesses usually invest,” Myron Orfield added. “It’s also impossible to have a functioning school district in a very poor city, which has made it much harder for Detroit to attract new residents.”

Several experts agreed that the intense segregation of the region is a primary cause of Detroit’s structural problems. Additionally, Orfield said, once a region is less segregated, it becomes easier to implement other regional policies because racial resistance is not as strong.

“After that, you had a hardening of positions, making it much harder to get anything else done,” he said. “A deeply segregated city is kind of a hopeless problem. It becomes more and more troubled and there are fewer and fewer solutions.”

Tax-base sharing

Orfield has studied the relationship between central cities and their suburbs and documented the problems associated with fragmentation, segregation, and sprawl. In Minnesota, he was instrumental in designing a system of tax-base sharing in the Twin Cities in the early 1970s.

Tax-base sharing has long been thought of as a way to reduce the disparities between a city and its suburbs. It can take several forms, but the Twin Cities system is often held up as a model. In Minneapolis-St. Paul, the 188 municipalities in the seven counties that make up the Twin Cities region pool 40 percent of the growth in revenue in its commercial-industrial tax base and redistribute the revenue based on population and property values.

According to Orfield, this has allowed the Twin Cities to avoid many of the problems that plague Detroit and other industrial cities, because new growth in one part of the region can subsidize other parts, depending on need.

Detroit’s tax-base had already fallen significantly by 1970, while the suburbs were experiencing strong growth. In his 1976 State of the State address, then-Governor Milliken proposed that the Detroit area adopt a similar model. “There was a recognition that the unequal patterns of growth were going to continue unless something was changed,” said Robert Kleine, who served as the director of the Office of Revenue and Tax Analysis for the State of Michigan under Milliken.

But Milliken’s plan was never even taken up in the state legislature. According to Kleine, suburban municipalities were deeply resistant to the idea. He acknowledged, too, that no one advocated strongly on behalf of the proposal from the city, and that Milliken did not press the issue in the face of that resistance and apathy.

“A more vibrant, vital city”

Had such a system been adopted, however, “What would have happened of course is that all the growth in the region, which was mainly in [neighboring] Oakland and Macomb Counties, would have been shared with the City of Detroit,” Kleine said. “That would have meant somewhat less revenue for some of the suburbs, but they would have done just fine. But Detroit would have had a substantial amount of additional revenue.”

As Remapping Debate has reported, the decline in Detroit’s tax base represents the greatest challenge to the city’s ability to sustain itself. It has responded to the loss in revenue by cutting services down to bare-bones and by raising taxes to the highest levels in the state. Kleine said that a regional tax-base sharing system would have mitigated the problem’s Detroit has faced with revenue.

Additionally, Orfield added, a fragmented system of taxation encourages individual municipalities to compete with one another by lowering taxes. “That competition has been very destructive in Detroit, because the city has had to keep its tax rates high to maintain services, while the suburbs have been able to draw people and investment out of the city by lowering taxes,” a process that encourages sprawl.

“If everyone knew that some of their new revenue was going to go back into Detroit,” Orfield said, “there would not have been the same incentive to compete with one another.” Instead, “the incentive would have been to compete together, as a region.”

“If we had gotten this done, Detroit would have been able to maintain adequate services and lower tax rates,” Kleine said. “It would have mitigated sprawl and flight. Detroit would almost certainly be a more vital, vibrant city than it is today.”

Re-imagining Detroit

While it is difficult to determine exactly how Detroit would look today had these measures been implemented, experts agree that the city’s financial and social problems would likely be much less severe.

“Right now, everybody is talking about how to stop the bleeding,” said Wayne State’s John Mogk. “That would be so much easier if regionalism had been adopted and followed in the ’70s. The patient would not be nearly as sick as it is today.”

It’s possible that, even if the missed opportunities of the 1970s had been taken advantage of, policy makers would not have implemented them in such a way as to be fully effective. And some of the processes that helped shape Detroit’s current plight may have continued. The movement of Detroit’s industrial base to other parts of the country, for example, would have been largely immune to regional solutions.

Still, Mogk said, if a combination of regional governance, tax-base sharing, and desegregation had been pursued by city, state, and suburban officials, it’s possible that Detroit could have decreased its reliance on the auto industry, which would have been beneficial not only for the city but for the suburbs and the state as a whole.

If the outward sprawl of the metro area had been reduced, “You probably wouldn’t have a thirty percent vacancy rate in the city. A lot of the neighborhoods that were stable then might still be there today,” Mogk said.

“There would probably be much less racial inequality today,” said Joe Darden of Michigan State. “You might not think of this huge racial distinction between the city and the suburbs.”

And, had it been able to maintain a steady revenue base, services in the city might not have decreased to their current, largely inadequate level, Kleine said. “The city would have had a much easier time attracting new investment and new residents because it would be able to provide them with a much higher quality of life than Detroiters have now.”

“I can’t think of a problem that Detroit is currently facing that would not have been solved, or at least very reduced, by these regional proposals,” Darden said. “The taxes, the segregation, the poverty, the school system — all of it.”

“When we talk about Detroit, we could be talking about a success story, a city that experienced all of these challenges and came out of them intact,” he went on. “Instead, we talk about an absolute failure of public policy.”