June 13, 2011 — Before the widespread use of antibiotics, infectious diseases were a major cause of illness and death. Thanks to the drugs, many of those diseases have been brought under control since the 1950s. But the misuse of antibiotics in humans and animals has yielded bacteria that are increasingly antibiotic resistant, and, as reported last week, the agriculture industry in the United States has remained firmly regulation-resistant in the face of calls to reduce or eliminate the non-therapeutic use of antibiotics in animals (for example, antibiotics used for promoting growth).

If the current trend continues, it appears that we are on the threshold of an era in which now-treatable infectious diseases re-emerge as frequent life disrupters, and, ultimately, as major killers (see box).

“We will slowly go back to the situation of the early 20th century when infectious disease was such a scourge that people didn’t live long enough for heart disease and cancer to be our biggest problems,” said Margaret Mellon of the Union of Concerned Scientists.

More complications

One consequence of increased antibiotic resistance is that more people will be more susceptible to life-altering complications from such resistance, such as organ damage, kidney failure, and lung injury, said Brad Spellberg, associate professor of medicine at the UCLA Geffen School of Medicine. He gave the example of a colleague who came down with diverticulitis, an infection of the intestinal lining. That colleague’s doctor gave him the standard antibiotic treatment, but it failed and the infection eroded his colon to the point that a hole was created in the colon wall. He had to have a colostomy bag for several months. “It completely and fundamentally changed his life,” Spellberg said.

Mellon also said she knew a colleague who contracted an antibiotic-resistant infection that did not respond to the first drug she was prescribed. In the time it took for her to return to the doctor for further treatment, the infection had spread to her kidneys. It took six months before she was finally able to get rid of it.

“A lot can happen in the several days that it takes for the doctor and the patient to determine that the first antibiotic that was given didn’t work,” Mellon said.

More hospitalizations and less successful treatment

More people will also have to be hospitalized for routine infections if the effectiveness of antibiotics continues to decline, Spellberg said.

Oral antibiotics have long been the standard treatment for urinary tract infections, which are diagnosed in one out of three women before the age of 24. But doctors are now seeing E. coli infections of the urinary tract that are resistant to all oral antibiotics, requiring patients to go to the hospital for intravenous antibiotic treatment, Spellberg said. If the antibiotics resistance rate in E. coli becomes high enough, then all patients with urinary tract infections would have to be hospitalized, he said.

And going to the hospital has itself become alarmingly risky. Already, 1.7 million people in the U.S. acquire infections in the hospital each year, resulting in 99,000 deaths, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The increased risks might be particularly acute for those who have a serious disease or who are otherwise especially vulnerable; treatment for cancer patients, people in intensive care, premature babies, and those in need of organ transplants, Spellman said, would all be “dramatically negatively impacted.”

More death

In the pre-antibiotic era, people who got a simple skin infection had a 10 percent chance of dying, and people who contracted pneumonia had a 60 percent chance of dying, Spellberg said.

While he didn’t think mortality rates from infectious diseases would become as high as they were in the days before antibiotics, Spellberg said it was reasonable to think that if we continue down the road we are on today, there will be an increasing number of pathogens for which we have no defense at all.

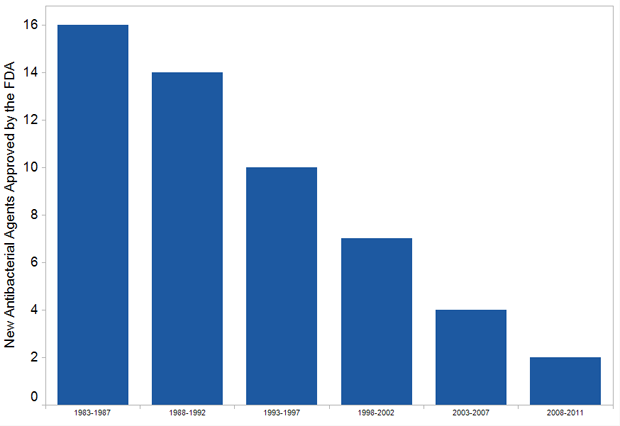

Mellon said the general public has a mistaken sense that there will always be options when an infectious disease does not initially respond to treatments — that doctors will somehow just raise the level of drugs, switch to a different drug, or try a combination of drugs if one doesn’t work. But the classes of antibiotics are limited, and new classes aren’t being developed. (Beyond the scientific difficulties, two hurdles are frequently cited: pharmaceutical companies not interested in the relatively low profits yielded by new antibiotics, and idiosyncrasies in the FDA drug-approval process as applied to antibiotics, see box).

“We’re scrambling,” Mellon said. “In some cases enough antibiotics don’t work that you can get to a point where there’s nothing left on the shelf.”

Antibiotic resistance, she continued, “will be a gradually accumulating kind of weight on our medical system that will increase costs, increase suffering, and decrease the tools we have, and finally that weight will get us.”

“People will die of these infectious and we won’t be able to treat them at all,” Spellberg said, adding that infectious disease will “drag down the average lifespan and result in a lower quality of life.”

The “return of our old enemies in an untreatable form”

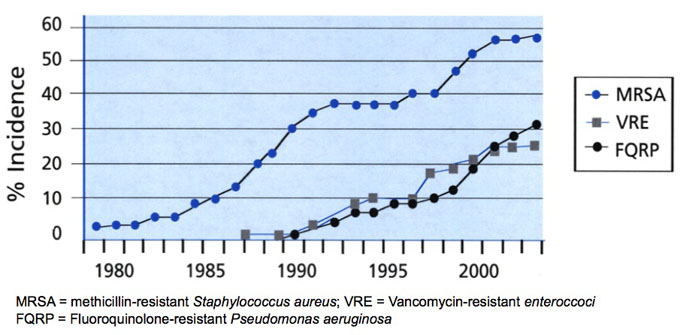

Ellen Silbergeld, professor of environmental health sciences and epidemiology at Johns Hopkins University’s Bloomberg School of Public Health, said the majority of new infectious diseases that have emerged in the last 40 years are caused by drug-resistant bacteria.

“E. coli is not new, salmonella is not new, staph is not new,” Silbergeld said. “But what is new are strains of these old pathogens that are now resistant to almost all classes of drugs that we can throw at them. It’s a return of our old enemies in an untreatable form.”

Alexander Fleming, who won the Nobel Prize in 1945 for his discovery of penicillin, warned in his acceptance speech of the danger of antibiotic resistance and the need to safeguard the drugs, Silbergeld said.

“Instead we did the opposite,” Silbergeld said. “Having been warned, having this knowledge, how could we permit the enormous range of unnecessary uses of antibiotics that we’ve done?”