February 3, 2011 — No one has done more than the billionaire private-equity investor Peter G. Peterson to stir America’s anxiety over deficits, debt, and what Peterson (among others) considers out-of-control entitlement-program spending. Those same concerns now lie at the heart of a “fiscal responsibility” curriculum being developed for America’s high schools. The curriculum bears the stamp of Columbia University’s prestigious Teachers College, but reflects the focus suggested by the Peter G. Peterson Foundation, which provided $2.4 million in funding for the project.

Teachers College gave Remapping Debate access to a set of 24 lessons set to be test-taught in four states this spring prior to a wider roll-out in 2011-12. Heavily weighted toward the themes and arguments of Peterson and other deficit hawks, the trial lessons could be seen as part of an effort by one of the country’s wealthiest men, now 82, to spread his gospel to coming generations. Although the lessons focus on the perils of public debt, they also suggest another danger — of an academic institution inadvertently lending its weight to a big funder’s cause.

The curriculum’s authors — a team of educators working under the supervision of Teachers College faculty — describe it as nonpartisan and “inquiry-driven.” Anand Marri, the assistant professor of Social Studies and Education in charge of the project, rejected the idea that Peterson and his foundation might be using Teachers College to promote an agenda. “People from the right and the left are going to find something wrong,” Marri said. “But the larger point of this curriculum is to get kids to think about multiple perspectives. We’re trying to give them as holistic a picture as we can.”

In their presentation of questions and selection of evidence, however, the trial lessons repeatedly point toward two core ideas of Peterson’s long crusade: first, that America’s future is threatened by deficit spending, and, second, that Social Security and Medicare have helped put our economy on an “unsustainable course.”

Debt and deficit, first and last

Andrew Fieldhouse, one of several economists asked by Remapping Debate to review parts of the 409-page curriculum, objected strenuously to what he said was a loaded discussion of the debt and deficit, one designed both to fuel alarm and to put undue focus on the spending rather than the revenue side of things.

Fieldhouse, a federal budget analyst at the left-of-center Economic Policy Institute, questioned the practice of treating taxes, spending and fiscal balance as issues unto themselves. “Budgeting is the numeric embodiment of all your national values and priorities,” he said. “It’s about the public goods you want to provide for the nation, and how you pay for them.”

The starting point of any discussion of public finances, Fieldhouse continued, should be a vision for the country and its future, and, within that framework, a conviction about the role of government. A curriculum conceived in that spirit, he said, would explore a range of possible government missions — providing social insurance, funding education, investing in infrastructure, easing people’s fears, strengthening communities, smoothing out the economic cycle — before it tried to tackle questions of debt financing and fiscal responsibility. The trial lessons, which plunge right into these questions, rest on “a problematically narrow-minded view of the economy,” Fieldhouse said.

Robert Prasch, an economics professor at Middlebury College, voiced similar complaints about the way the curriculum deals with Social Security. “No effort is made to explore whether, and to what extent, there may or may not be a fiscal crisis facing Social Security,” Prasch said. “It is presumed or taken as an unimpeachable fact.”

In its discussion of Social Security and other issues, the curriculum does sometimes cite materials from liberal as well as conservative sources, but the effort to provide balance is often brief or oblique. The first of five economics lessons, for example, cites a proposal to gradually eliminate the social-security-tax income cap, which currently stands at $106,800 a year. That step alone, the economist Teresa Ghilarducci is quoted as saying, would “solve the entire predicted Social Security deficit for 75 years.”

Out of four Social Security remedies laid out for consideration, however, hers is the only one that would not mean lower benefits for at least some recipients. Moreover, the lesson fails to provide what Ghilarducci and other retirement-policy experts regard as an important piece of background information: the fact that because of rising income inequality, the Social Security tax now covers only about 84 percent of all payroll income, down from the 90 percent target set by a reform commission in 1983.

By leaving that out, Ghilarducci told Remapping Debate, the curriculum creates an exaggerated impression of Social Security’s vulnerability. The same effect is created, she said, by repeated cases in which the lessons lump Social Security with Medicare and Medicaid, two programs that face far more serious long-term problems.

James Galbraith, professor of government at the University of Texas, pointed out that the lesson containing Ghilarducci’s proposal leads off with an “essential question,” namely: “Should mandatory programs like Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security be modified to address the national debt?” Not, “What is the national debt? Is it a problem?” Galbraith said. “Not ‘Should anything be done to address the national debt?’ Just ‘Should Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security be modified to address the national debt?’”

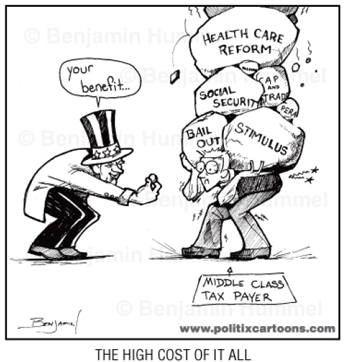

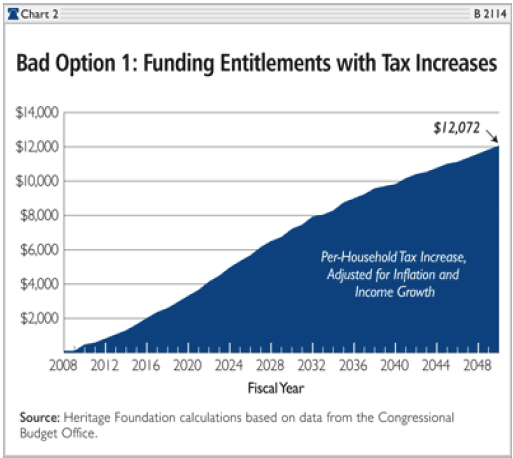

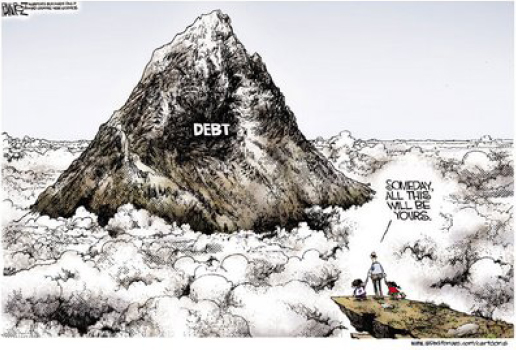

Driving home the point

Students might be led to answer “yes” after browsing over the series of worrisome graphs, charts, and visual materials that accompany the chapter. Among them: a cartoon depicting a middle-class taxpayer staggering under the weight of “the programs piled on the taxpayer’s back” (see cartoon at right); charts showing U.S. debt at historically high levels and illustrating the hefty share of federal spending taken up by Social Security, health programs, and defense; a graph suggesting that current spending trends are “not sustainable”; a second cartoon depicting a parent having to tell his young child that a towering and ominous mountain of debt will someday “all be yours” (see cartoon at bottom of page); and a second graph (this one supplied by the conservative Heritage Foundation) purporting to demonstrate the apparent futility of trying to address the entitlement programs’ problems with tax increases (see graph below). The last point is reinforced by the graph maker’s decision to present the cost of such tax increases as rising to the point where, by the year 2048, it would amount to an extra $12,078 “per household,” suggesting that the burden might fall equally on all households. That would only be the case, however, if the U.S. had meanwhile chosen to abandon its longstanding commitment to the principle of progressive taxation, in which high earners pay a bigger share of their income than lower wage earners do.

The difficulties of raising sufficient revenue to make a serious fiscal difference are dramatized again in Lesson 3, “Taxation and the Federal Budget.” Here, all except one of the proposed tax measures — “Return the Estate Tax to levels set in 2001, before the Bush tax cuts” — involve personal income taxes. The lesson does not consider higher corporate taxes (or fewer corporate tax breaks), a financial transaction tax, or taxing capital gains as ordinary income — three options with the potential to raise large sums of money and make a major dent in the deficit without raising the tax obligations of the vast majority of Americans.

Remapping Debate raised these questions, and others, with Professor Marri. In a number of the specific cases cited, the lessons might appear to be skewed or lacking important context, he acknowledged. But the curriculum is a work in progress, Marri added, and such problems will be addressed as time goes on.

How? Sometimes by adding a fact, sometimes by changing the sequence of material, sometimes by inserting a qualifying phrase such as “Some economists say…” That, for example, was how Marri proposed to deal with a passage in an introductory piece declaring that “our existing tax structure and government spending patterns, the rapidly rising cost of the way we deliver health care, and our mandated commitment to provide Medicare for a ‘booming’ population of retirees age 65 and older have put our economy on an unsustainable course.”

“The current budget deficit is $1.4 trillion or about 10% of the nation’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of $14.5 trillion,” students learn at the beginning of Lesson 6, entitled “The Federal Budget and the ‘Graying’ of America.’” Remapping Debate asked Marri about the failure to link those striking figures to three factors that go a long way toward explaining them: the tax cuts of 2001 and 2003, the unfunded wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and the revenue declines and spending increases occasioned by the severe economic contraction of 2008-09. The curriculum’s authors are preparing a lesson on the Bush tax cuts, Marri answered. But he added that they had generally chosen to downplay events of the recent past, because “we didn’t want the lessons to get outdated.”

How was the project created?

It was Teachers College that approached the Peterson Foundation, at first with the idea of a curriculum based on a Peterson-sponsored documentary, “IOUSA.” Originally, the focus was going to be on personal finance. But the Peterson foundation preferred to emphasize public finance. The foundation, as it happened, had a far bigger project in mind than the one envisioned by Marri and his colleagues: their $50,000 application ended up as a $2.4 million grant for a curriculum focused on the federal budget, the national debt, and the deficit. “These are three things that are important for kids to know about,” Marri said, adding that the choice of those particular topics was “how we got this project.”

Marri pointed out more than once, however, that students would be encouraged to think about how to “address our fiscal challenges in a manner that is consistent with our values and traditions — that’s the essential question of the curriculum,” Marri said.

The decision to make “fiscal challenges” the frame within which values are discussed is different, of course, from Andrew Fieldhouse’s proposed alternative — one that begins with values, traditions, and societal goals and choices, and then, within such a policy framework, assesses how to fund those choices most appropriately.