March 2, 2011 — As recently reported by Remapping Debate, little is being done to deal with the crisis in medical care that will result from the massive physician shortage that is just around the corner. Even if policy-makers begin to address this long-avoided challenge in the near future, the country will still feel the consequences of the shortage over the next decade, since it takes at least several years to ramp up an adequate and sustainable pipeline of new physicians.

So what can be done in the short-term? A leading proposal is to rely more on nurses as the physician shortage grows worse.

Advanced practice nurses — a category that includes nurse practitioners, nurse anesthetists, nurse midwives and clinical nurse specialists, and is often extended to include physician assistants — would be allowed to operate with greater autonomy, and, in some cases, entirely independently of physicians.

Currently, most states restrict what state licensing boards call “scope-of-practice” — that is, each state’s definition of exactly what types of care a specific license allows a nurse to perform.

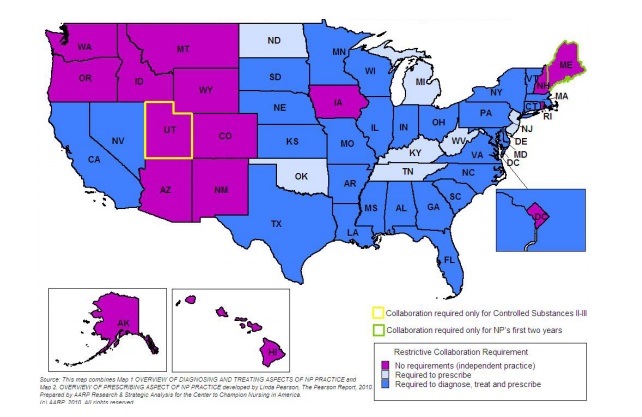

For example, many states — including California, Texas and New York — do not allow nurse practitioners to diagnose illnesses or prescribe medications without the direct supervision of a physician. In other states — like Michigan and Oklahoma — nurse practitioners are allowed diagnose, but not to prescribe. On the other hand, in 14 states — including Oregon, Montana and New Hampshire — nurse practitioners are allowed to do both without physician supervision. (See map at the bottom of the page.) Additionally, restrictions sometimes vary regionally within a state, with nurse practitioners practicing independently in rural areas and under the supervision of a physician in cities.

But the training for advanced practice nurses, who must earn either a master’s degree or a doctorate in their field, does not vary substantially from state to state, leading many to conclude that the varying scope-of-practice restrictions are caused more by political differences than by safety concerns.

Practicing at the top of one’s license

Advocates for removing scope-of-practice barriers in restrictive states argue that the limitations are illogical and wasteful, and that all nurses should be able to practice “at the top of their license” — meaning to the full extent of their training.

“I think the evidence is in place that given that we’re educating everybody to a particular level and they are passing certified exams, there is some waste of healthcare delivery capacity when states restrict the ability of nurses to practice at the top of their license,” said Catherine Gilliss, president of the American Academy of Nursing (AAN), a group that has long advocated for allowing nurses more autonomy.

This perspective was given a major boost last year, when the Institute of Medicine published a much-anticipated report called, “The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health,” which recommended, among other things, relaxing some state restrictions on nurses’ scope-of-practice.

Susan Hassmiller, the senior adviser for nursing at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the study director for the report, said that there is no evidence indicating that quality of care suffers when advanced practice nurses work without physician supervision, and pointed out that the Institute of Medicine follows strict research standards when making recommendations.

Indeed, she said, research indicates that patient outcomes do not change dramatically regardless of whether a physician or an advanced practice nurse delivers primary care.

Physician resistance

Efforts to lift state restrictions on nurses have met with significant opposition, however, mostly from groups representing physicians, such as the American Medical Association and the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), who argue that nurses do not receive sufficient training to take on responsibilities that have traditionally been the domain of physicians.

“Granting independence is going the wrong direction,” said Perry Pugno, director of the division of medical education at the AAFP. “They simply don’t have nearly enough training. It would be irresponsible.”

Much of the debate centers on training. AAFP has reported that family physicians receive a minimum of 20,700 hours of training during medical school and residency. The highest level of training available for a nurse, by contrast, requires no more than 5,350 hours of training, a difference of nearly 75 percent.

Pugno agreed that there are things that advanced practice nurses are well-trained to do, including handling simple acute issues, like ear infections, and stable chronic illnesses, like controlled asthma. He maintained, however, that nurses do not have the training required to “go beyond the straight-forward” and treat patients with multiple illnesses or irregular symptoms that require a nuanced diagnosis.

He gave the example of a sore throat. When a nurse sees a patient with a sore throat, he said, it is within the nurse’s capacity to consider a handful of diagnoses, such as a virus or strep throat. A physician, alternatively, would consider a broader range of potential causes, like a retropharyngeal abscess, gonorrhea, and diphtheria.

“Similarly, the physician has the training to bring a wider range of therapies to the treatment plan, a wider knowledge of how those therapies affect other health conditions or medication regimens the patient may have, and the expertise to blend therapies so the patient has the best outcome for one condition without complicat[ing] another health issue,” he continued in an email.

Additionally, many physicians, including Gary Floyd, who has served on the Texas Medical Association’s Council on Legislation, have called attention to fundamental differences in the way nurses and physicians are trained. They point out that, while physicians receive substantial scientific training on disease and anatomy, nurses’ training tends to focus on “care and comfort.” The lack of scientific training in nursing education, they argue, means that, when it comes to diagnosing and treating disease, patients are better off in the hands of a physician.

“I think there is a fundamental difference between nursing school curriculum and medical school curriculum,” said Floyd. “Most of the physicians I know did not learn the specifics of diagnosing and treating a patient until residency.”

Floyd added that the years a physician spends in residency training is the time when “you see a lot of what’s normal, and the more normal you see, the easier it is to pick out what’s not normal.”

But Hassmiller argued that the vast majority of Americans have very basic primary care needs that could be handled by nurse practitioners, especially in the absence of doctors. And Gilliss of the AAN argued that part of nurses’ education is training them to understand what issues they are prepared to handle, which they are not, and when to consult a physician.

Pugno asserted, however, that knowing when a patient’s needs exceed the capacity of a particular healthcare worker is yet another thing that physicians are better trained for than nurses.

“It’s not a matter of trust,” he said in an email. “It’s a matter of threshold and perspective, both of which are lower and narrower for nurses compared with physicians.”

Floyd added that it is especially important in the primary care environment for a healthcare worker to be able to recognize when a simple-seeming problem is actually more complicated.

But Michael R. Bleich, the dean of the School of Nursing at Oregon Health & Science University, said that he saw the prospect of a large segment of the population receiving no care at all as the physician shortage intensifies as being “much scarier” than the idea that nurses would not be able to make that distinction and potentially misdiagnosis an illness.

The real question, he said, is “[S]hould we provide no care or should we allow nurses to move into that arena?”

Hassmiller agreed, and pointed out that nurses are already stepping up to deliver primary care in the absence of physicians.

“There are plenty of areas in this country where the shortage of physicians is so acute that the only provider the population has access to is a nurse practitioner or a physicians’ assistant,” Hassmiller said. “That’s the reality.”

A comprehensive policy instead of “zero sum”

Robert Phillips, director of the Robert Graham Center, a research organization that is sponsored by the AAFP, agreed that, as the physician shortage intensifies, nurses should play a heightened role in healthcare delivery.

He worried, however, that relying more heavily on nurses could effectively waylay plans to train more primary care physicians. The anxiety of primary care physicians — that they stand to be replaced by advanced practice nurses — has been reinforced by some recent reports calling for physician training resources to be diverted away from primary care and toward specialty medicine.

Bleich argued that giving nurses a greater role in the short-term would not necessarily involve substituting advanced practice nurses for primary care doctors.

“One of the big myths that gets perpetuated is that nurses are trying to take the place of physicians,” he said, “and that’s just not the case. There is an overlap, which is a positive thing for patients.”

When asked if giving nurses more autonomy meant less of a role for physicians, Hassmiller said, “We certainly hope not. Our position is that we need more nurses and more primary care doctors.”

But Phillips pointed out that there is already a shortage of so-called “bedside nurses,” or nurses that have not received advanced training, and that incentivizing more nurses to pursue advanced degrees would exacerbate that problem, essentially shifting the shortage down the line.

Researchers have demonstrated that the dearth of nurses will likely grow even worse than the projected physician shortage; they estimate that there will be 260,000 too few nurses by the year 2025.

It isn’t enough to produce more physicians, or more nurses, Phillips said. The U.S. will need to do both. “We need to be looking at getting supply and distribution right for physicians, nurses, and all other members of the team,” he said.

And the body of evidence on the subject indicates that, when both advanced-practice nurses and primary care physicians are practicing in a healthcare delivery environment, referral rates and costs go down while patient outcomes improve. Advocates on both sides of the issue agreed that this is the best-case scenario for a delivery model in the future.

Gilliss said that it was certainly within the country’s capacity to meet all of the healthcare workforce needs in the long term, and that producing more nurses should not mean producing fewer physicians.

That would mean ramping up training for physicians, advanced practice nurses and bedside nurses simultaneously. One of the foundational pillars of the Institute of Medicine report, Hassmiller said, was that educational opportunities should be increased for nurses in all fields.

Additionally, Gilliss said, when viewed from a patient-centered perspective, a policy that sought to produce more healthcare workers across the board would carry significant advantages for the public.

“Right now, there’s a service that people aren’t getting,” she said. “That’s the coordination of care [between healthcare professionals].” If there existed the capacity for some nurses to be in charge of organizing every patient’s healthcare, the quality of care would improve, as well as the patient’s experience, she said.

Gilliss maintained that viewing healthcare workforce policy as a zero-sum equation where either doctors or nurses are forced to lose out would be a mistake, and that the U.S. should strive to produce more physicians and more nurses. She said that increasing education and training would come with costs, but that the costs of a long-term shortage of physicians or nurses would be greater.

“I think it would be silly to assume that adding more [healthcare workers] would not cost more,” she said. “It’s a matter of priorities.”

Needing a different starting point?

Disputes that pit doctors against nurses will likely continue, Gilliss said, as long as the discussion is premised on the need to cut costs, rather than on the need to improve the care delivered to patients.

A similar roadblock has also been apparent in the debate over the burgeoning physician shortage. There, too, the lack of political will to come to grips with the cost of meeting the growing medical needs of an aging and growing population has stymied action.

In both the long-term and the short-term, Gilliss said, the place to start is with an evidenced-based discussion of what strategies will bring the best care to the most patients.

Next week: the pros and cons of trying to meet the doctor shortage by increasing reliance on medical graduates and practicing physicians from other countries.