Nov. 9, 2011 — The many impacts of unemployment — including social and psychological ones — have long been catalogued. But much less is known about the consequences of “underemployment.” Millions of Americans — at least as many as are unemployed, and perhaps more — have either been forced to take part-time work because full-time jobs are not available, or are forced to work in jobs for which they are overqualified. (See “How many are there,” below.)

“We have never experienced anything like this,” said Carl Van Horn, director of the John J. Heldrich Center for Workforce Development at Rutgers University. It is “not something that as a society we’re used to dealing with.”

Since the recession, researchers have begun to take more of an interest in the psychological effects of underemployment, and what they have found is not encouraging. In the short-term, it appears that those who are underemployed — like those who are unemployed — have an increased risk of depression, increased stress, and lowered self-esteem.

And there may be long-term negative effects, too. On the psychological side, there are intriguing hints of a downward spiral that might affect underemployed workers in their family, social, and employment relationships. In economic terms, there is already data that show that the effects of being underemployed directly after graduating from college can linger for more than 10 years.

“Unemployment is an emergency,” Van Horn said. “Underemployment is a crisis.” Nevertheless, the United States, unlike other countries, is not gathering the data needed to pinpoint what the full costs of underemployment actually are. Making it difficult to know which policies might be effective in helping those affected.

What’s wrong with me?

Douglas Maynard, an associate professor of psychology at the State University of New York in New Paltz is one of only a few psychologists who has studied the mental health effects of underemployment.

“There are a few things that we know for sure,” he said. “We see very clear evidence of lower self-esteem, greater stress, and less job satisfaction,” he said.

To illustrate those effects, David Pedulla, a doctoral candidate at Princeton who is writing his dissertation on the consequences of underemployment, suggested considering the case of a worker with a degree in accounting who is laid off from an accounting firm and has to take a new job working in retail.

“Imagine going from a situation where you had gained some status and control over your day-to-day life, and then moving into a retail job with a boss with less education than you,” Pedulla said. “That person might feel like he had lost control over his life.” The theme of loss of control is one that numerous experts cited repeatedly.

Pedulla said that the result is often that underemployed workers internalize a sense of shame, and begin to blame themselves for their situation. Psychologists have long recognized that shame is a very powerful emotion, and that people who feel a strong sense of shame tend to cope with it in different ways. (See bottom box on the nature and power of shame.)

The ex-accountant working retail, Maynard said, “might start blaming himself for it. He might wonder, what’s wrong with me that I’m here?”

That sense of shame intensify if the individual has been forced to take a pay cut, Maynard said. Underemployed workers will often feel a greater financial strain, which can be exacerbated because their new jobs may not provide the same levels of health or retirement benefits as their old jobs, while at the same time making them ineligible for government assistance programs.

Pedulla said that, for men, the implications of becoming underemployed and earning less money can have profound effects on their perception of their masculinity, especially if they find themselves struggling to provide for their families.

“The breadwinner model is still very present,” he said. Men who feel that their masculinity is being threatened are more likely to lash out at their families. There is evidence that underemployment can cause marital strain, Pedulla said, and that when older children perceive that there has been a reduction in income or status, they may “inherit” the sense of shame.

“Kids may feel like they can no longer have the newest clothes, or that they can’t do certain activities with their friends because their family can’t afford it anymore,” he said.

Social isolation

One of the strongest effects of the shame and lowered self-esteem that can result from underemployment is that the worker may become socially isolated — in the workplace and outside of it — and that the isolation can, in turn, reinforce those feelings because the worker is not receiving social support, experts said.

“Your social interactions might change,” Pedulla said. “If you were laid off from a job where you had friends, you might feel less inclined to see your former co-workers because you might fear that they would look down on you.”

Some research has found that workers who have been laid off and found new jobs that are unsatisfactory are less likely to engage in social activities. In 1988, Katherine Newman, a sociologist and the current dean of the School of Arts and Sciences at Johns Hopkins University, wrote an influential book called Falling from Grace: Downward Mobility in the Age of Affluence, in which she interviewed hundreds of people who had, for various reasons, fallen out of the middle class.

Several people reported that the social consequences of underemployment can be particularly challenging.

“If your old friends are going out for drinks or going to the theater or playing golf or doing other things that you can no longer afford to do, then that can be a very isolating experience,” she said.

Berrin Erdogan, an associate professor of management at Portland State University, said that underemployed people might find themselves isolated within the workplace as well. “You would probably feel like a misfit, especially is you are surrounded by people who are less educated than you,” she said.

She used the example of a young worker who graduated from college but could not find a job in her field, and had to start working at a coffee house. “After work, [your co-workers] might go out or spend time together on the weekends, but you might be less inclined to go because you feel like you don’t fit in,” she said. “At the same time, there’s a great chance that your co-workers might feel intimidated by you, and won’t want to invest in a relationship with you.”

Erdogan said that that situation could quickly lead to anger and “self-defeating behavior,” which could affect the way that underemployed workers do their jobs. “If you don’t feel appreciated in your job, and feel like it’s unfair to be there, you might not do your job as well. If you’re working in a coffee house, in the end you may not end up treating your customers very well,” she said.

In his research, Maynard has found that workers who perceive themselves to be overqualified for their jobs report less job satisfaction even than workers who are involuntarily employed part-time.

Erdogan said that evidence also exists that workers who are overqualified for their jobs are more likely to have bad relationships with their managers and co-workers, and that this can make them more likely to get fired from their jobs.

“If you don’t leave a job on good terms,” she said, “that in turn diminishes your chances of finding another job.”

Depression and boredom

Psychologists stress that the duration of underemployment is a very important factor. If a person finds a better job within a few weeks or months, said Daniel Feldman, associate dean of the Terry College of Business at the University of Georgia, the negative psychological impacts are more likely to be limited.

But if the worker remains underemployed for more than six months, Feldman said, it would be a short step from the combination of boredom and self-doubt to clinical depression. Researchers have shown that depression is strongly associated with underemployment, especially if the person is making less money than he or she had come to expect. Others have also found that underemployed workers are just as likely as the unemployed to show signs of depression.

Going back to the example of a worker who went from an accounting job to a retail job, Feldman said that an huge factor would be the dissonance in the worker’s mind between his present situation and the future that he had imagined.

“You went from doing something where you were using your skills to folding shirts,” he said. “That’s a very strong contradiction [of] the idea that you had of where you were going to end up.”

“You’re going to be constantly bored with that job,” he said. “You’re never going to be happy working there.”

Depression has long been linked to self-destructive behavior such as an increased incidence of alcoholism, drug use, aggression toward family members, and suicide. While little research has been done examining the incidence of these behaviors among underemployed people, the connection between self-destructive behavior and unemployment is quite strong.

“We would expect to see many of the same effects in some underemployment situations,” said Meghna Virick, an associate professor of management at San Jose State University.

Feldman has also found that if workers who are laid off blame themselves for losing their jobs, there is an increased likelihood that they will engage in self-destructive behavior.

Characteristically, people who suffer from depression can have strong feelings of shame, guilt and worthlessness, as well as fatigue and irritability. They can also lose interest in things that were once important to them, such as their families, friends, and hobbies.

“People spend a huge number of their hours at work,” Pedulla said. “It’s central to the construction of their identity. If that work is making them depressed, then it’s easy for that to affect other parts of their lives.”

Unfulfilled hopes and diminished expectations

Though many researchers speculate that underemployment can have long-term psychological effects, it is an issue that has not been studied in depth. But several experts worried that, if the situation does not improve quickly, it could lead to a sense of unfulfilled hopes and diminished expectations, especially among young people.

“If you’re going into the labor market and have a particular idea of what your future is going to look like, and what you actually find is quite different, that has an effect on how you perceive yourself and how you perceive your chances for the future,” said Sarah Anderson, a professor of psychology at the University of South Australia who has long studied underemployment.

Returning to the example of the ex-accountant who works in retail, Feldman said that after a certain amount of time the worker might start to become discouraged. “If you don’t get out of the job after six months, you become increasingly pessimistic that you’re going to get out of it at all,” he said.

That could mean that the worker stops looking for other jobs, or approaches the job search with “less gusto,” Maynard said. Because the job search can quickly become an exhausting process, especially while an applicant is working at another job, he or she may not put in as much effort after a prolonged period of time, he added.

“Some people might cope with being underemployed by changing their expectations, and saying, ‘I guess this is as good as it gets for me,’” Maynard said.

The job search can reinforce that sense. Several experts in management said that employers might be less likely to hire an applicant for a job if the applicant has been clearly underemployed, leading to a vicious cycle from which the worker cannot extricate him or herself (see sidebar).

If the worker is ensnared in this vicious cycle, Maynard said that he or she might begin to feel a sense of “learned helplessness” in which the person stops trying to actively change his or her situation. “If you’ve been applying to jobs and hearing nothing back, you may start to feel like you have no control over your life,” he said.

And many researchers have noted that the mental health effects of underemployment are most severe if workers feel that they have lost control over their situation — if they begin to feel trapped in their current jobs. “That is the point when we would expect to see the worst mental health outcomes,” Maynard said.

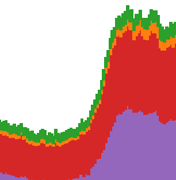

In the current context, that is particularly disturbing. There is some evidence that shows that during a recession, workers are less likely to quit their current jobs, because they are less likely to believe that they will be able to find another one. Before the recession, an average of three million people quit their jobs each month; in September, that number was slightly over two million. (See data visualization.)

Lack of data

While the understanding of the consequences of underemployment is growing, many of the experts interviewed for this article said that there is still a long way to go.

“There is much less empirical research than we would like,” said Pedulla. “Before we know how to respond effectively, we need to understand the contours of the problem better.”

One reason why so little research is done on underemployment is that it is important to have what’s called a “longitudinal” data source to draw from, which means data that follows individuals through time to measure what effects result from changes in their situations.

While the U.S. does have a few longitudinal data sources, they are generally limited in the amount of information they contain. Much of what is known comes from data from other countries, especially in regard to mental health and to more subjective measures like perceived well being.

Longitudinal data collection is more expensive and more time-consuming than normal survey studies, and while a few universities have the resources to conduct them, the responsibility generally falls to the government to provide the funding and support. Virick of the San Jose State University said that the recession should have served as a wake-up call to policy makers that this is an issue that demands attention.

“We haven’t had any kind of organized response to this,” she said.

According to Erdogan, the United States is paying much less attention to the issue than European countries. “In Europe, underemployment is treated as a social problem. We don’t even pay attention to it that much.”

Whose fault is it, really?

Few people would suggest that mass underemployment is somehow the “fault” of the people who are underemployed.

“Underemployment is now a structural feature of our society,” said Newman of Johns Hopkins. “Structural problems demand structural solutions.”

Nevertheless, several researchers said that, in the United States, there is a strong impulse for underemployed workers to blame themselves for their situation, which is the source of many of the negative mental health effects associated with underemployment.

“If people don’t understand that there is a way that the system has become rigged against them, they may start feeling like they’re to blame for their issues,” said Anderson of the University of South Australia.

Anderson said that appreciating the broader structures that created underemployment was an important part of a strategy to avoid falling into the trap of self-blame.

“I like to hope that we’re starting to see people realize that the ways the workplace has changed in the last few decades have not been positive for most workers, and to try to change that” she said.

Newman agreed. Seeking to address the systemic causes of problems “can be a very healthy coping strategy,” she said.