October 12, 2010 — On the evening of Sept. 27, 1960, after a day of barnstorming up and down Ohio’s industrial Lake Erie waterfront, John F. Kennedy arrived at the Municipal Auditorium in Canton. The night before, Kennedy had sparred with Richard Nixon in the first televised presidential debate in the nation’s history, and his supporters were in an exuberant mood: The New York Times reported that a “screaming audience of 5,000” filled the auditorium to cheer him on.

Kennedy’s speech that night was optimistic, but it was also urgent. The post-war boom had waned, he warned, and jobs were being lost: national unemployment stood just above 6 percent; in some places, it had been stuck at 9 or 10 percent for two or three years. Like the stand-offs in Formosa and Berlin, this was a crisis — brought about by advances in automation that had displaced coal miners and textile laborers, he said, but also by the Eisenhower administration, which had pursued a policy of tight money even as steel foundries and laborers alike lay idle. Kennedy’s message was pure post-war Keynesianism: “It is time that our economy was stimulated rather than was held back,” he said, “if we are going to maintain full employment in the United States.”

To modern ears, Kennedy’s speech is full of anachronisms. Our challenges overseas are not in Formosa and Berlin but Iraq and Afghanistan, and the jobs we worry most about are not in coal mines but on factory floors and in tech labs. But what has changed most may be our sense of what represents an economic crisis, and what our government can, and should, do in response.

For the past 18 months, the nation as a whole has faced unemployment of about 10 percent; in harder-hit areas like Vero Beach, Florida, and Fresno, California, the rate stands above 15 percent. Across the country, nearly 15 million would-be workers are now without jobs. Bringing the rate down to 6.1 percent, where it stood when Kennedy spoke in Canton and again 48 years later, as the financial crisis began, would mean creating more than 5 million jobs. Achieving “full employment” — a term that has largely fallen out of favor, but that generally refers to unemployment rates of 5 percent or less — is an even larger task.

Yet the prospects for decisive action — while brighter now than they were even two weeks ago — remain uncertain, and habits of thought acquired since Kennedy spoke seem to have lost little of their power. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the halting response by the Federal Reserve — the nation’s central bank, and the most powerful economic institution in the country, charged not only with controlling inflation but also with achieving maximum sustainable employment.

The Fed’s obligations are often in tension, and since the 1970s, when an overly expansionary approach led to spiraling prices and wages that damaged the economy, central banks have generally focused — with great success — on maintaining low inflation. (The Fed does not state a goal publicly, but its implicit target is understood to be about 2 percent.) In the current climate, though, an increasingly broad range of economists, from small-government libertarians to those on the center-left, has argued that the equation is reshuffled. While they disagree about other strategies — liberal economists, for example, tend also to favor more fiscal stimulus from Congress — this group agrees that one important way to spur growth and boost hiring is through aggressive action explicitly designed to create higher (though still moderate) inflation.

Such a move would be consistent with historic periods of growth, with what top Fed officials have prescribed for other countries in the past – even, in important ways, with how many of the Fed’s top officials have diagnosed our current woes. And it would echo the dramatic moves the Fed took to prop up the financial system at the height of the crisis. It would, also, however, violate what one economist, Laurence Ball of Johns Hopkins University, calls the “dogma” of low inflation.

Indeed, when Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke delivered his address on economic policy at the bank’s annual conference in Jackson Hole, Wyoming in August, there was just one course of action he specifically rejected: the targeting of a 4 percent inflation rate. While inflation was in fact too low, Bernanke said, such a move would risk “squandering the Fed’s hard-won inflation credibility.” Instead, he outlined several other moves the bank might take — though only if things were to get worse. When, three weeks later, the Fed’s top policy-making body issued its most recent statement, the message was the same: the economy was weak, inflation was too low, and the bank might, at some point in the future, “provide additional accommodation if needed.”

How did we chart this course, from 6 percent unemployment representing an emergency to a rate of nearly 10 percent being accepted — however much it is deplored rhetorically — as the best we can do? Economic thinking has changed dramatically since Kennedy spoke, but it is hard to trace a straight line between the academic arguments of the intervening decades and the current fatalism. The best answer may be that, when central banks learned how to tame inflation, they learned the lesson so well that the taming response became reflexive. For today’s Fed to seek a moderately higher rate of inflation — no matter how well such a move accords with the analysis outlined by its own leadership — it would have to cast aside the medicine it knows how to administer, and to do so in the face of a determined minority that offers a host of competing explanations for our current troubles.

And so, while the central bank can point to a number of steps it has taken, it has, in the eyes of many observers, done far too little. If he’d been told in 2008 what the economy would be like today, Ball said, “I would say of course everybody would view that as a crisis that would have to be addressed very aggressively. I don’t quite understand why there isn’t more of a crisis atmosphere.”

Ball’s recent research focuses on a phenomenon known as “hysteresis,” or the tendency of patterns to become self-reinforcing. Hysteresis has been observed in electromagnetic systems, in cells that are dividing, even in chromosomes. Ball’s contribution, following earlier scholars, was to show that it occurs in unemployment rates too — that a sudden spike in joblessness, if left unaddressed, can become permanent, even after the economy recovers. (Differences in regulation don’t seem to explain much — both heavily regulated European labor markets and their laissez-faire counterparts in Latin America have experienced hysteresis.) And while the mechanisms behind this trend aren’t entirely clear — the loss of skills and motivation that come with being unemployed for long periods is one likely, if unproven, candidate — the imperative it creates is: policy-makers should do all they can not to let elevated unemployment persist.

So why might inflation help? Inflation is often defined as too much money chasing too few goods — if the amount of money in circulation goes up but the underlying value produced by the economy stays the same, prices will rise. One of the problems with our economy today, though, is that there’s too little money moving around. Beginning in fall of 2008, individuals, businesses, and banks stopped spending money and started hoarding it. In effect, that money disappeared from the economy. The result of this “excess demand in the market for money,” explains Karl Smith, an assistant professor of economics at the University of North Carolina, is “a lack of demand in all [other] markets.” One result: businesses are producing less than they could. Another result: they’re doing it with fewer workers.

What we need, Smith said, is to “increase the money supply” — to put more actual money into the economy. Normally, when the Fed wants to do this it can lower interest rates to encourage borrowing, but those have already been brought near zero. Another method to bring real rates down further in the short term would be to reduce the future cost of repaying debt that people take out today, a fundamental effect of inflation.

Other economists – including Scott Sumner, an economist at Bentley University in Massachusetts, and a self-described “inflation hawk” – have outlined another benefit that moderately higher inflation could provide under the current circumstances. Because Americans had expected prices to continue going up about 2 percent a year (the norm since the early 1990s), they made economic decisions (like contracts they signed, and debt they incurred) based on that expectation. Thus, it was a shock when, in 2008, that trend was disrupted, and prices abruptly fell, or simply rose in some sectors much slower than expected.

Suddenly, people who had things to sell — homes, commercial goods, their labor — found themselves in a hole, which only increased their demand for money. If prices were to start rising again by 2 percent a year, they could arrest their economic slide: the deviation between what they planned for and what actually happened wouldn’t grow worse. But they will not eliminate the gap between their expectation for price rises of 2 percent per year and the reality of prices below that level unless extra inflation – that is, inflation beyond the level they had originally anticipated – is generated to fill the hole that developed in recent years. Anything less than that, Sumner says, amounts to “digging sideways.”

Just how, and how quickly, the Fed might create higher inflation is a matter of some debate, but there is reason to believe that were the bank to articulate publicly its plan, it would make a difference. And under the circumstances, Smith believes, setting a higher inflation target now — along with a credible commitment to keep the money stock high even after the economy recovers — is “probably the most important policy change you could make.” He maintains a list, dubbed the “4% Club,” of other economists and commentators who support the move.

Such an approach would be distinctly at odds with the Fed’s past practice; indeed, the Fed over the last two decades has been skittish anytime inflation tops even 3 percent. But while it’s true that poorly run economies often have very high inflation, the evidence for the harm of moderate inflation is much less clear. One 1995 study, for example, estimated that an increase of 10 percentage points in inflation corresponded to a reduction in annual growth of about 0.2 to 0.3 percentage points. Laurence Ball notes that after Paul Volcker, Greenspan’s predecessor, broke the runaway price increases of the early ‘80s, the inflation rate was maintained at about 3 or 4 percent — a level that the central bank won’t consider fostering now — for much of the rest of that decade. “Maybe there was some subtle way that 4 percent inflation was undermining the economy, but people didn’t seem very worried about it,” he said. Smith, meanwhile, has compiled data showing that price acceleration and job growth tend to move in tandem.

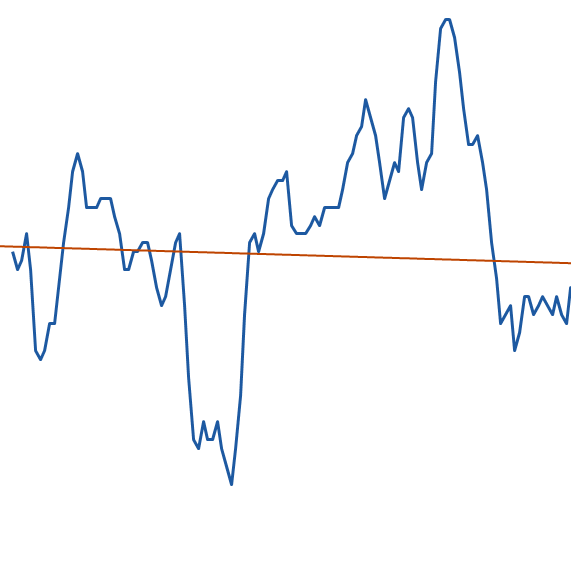

Too much acceleration can be a dangerous thing, of course, especially from a higher base. But as the chart titled “Inflation Rate 1983-1994” shows, during the mid-1980s the rate remained at moderate or low levels for a number of years, then briefly crept up to about 6 percent at the end of the decade. The Fed was subsequently able to bring the inflation rate down quickly, and it has remained at lower levels ever since.

While the argument for higher inflation now seems out of the mainstream, a look back to the late 1990s, when Japan encountered a macroeconomic situation that many economists worry is broadly similar to the one America faces today, is instructive. Milton Friedman — the conservative economist and Nobel laureate who is generally credited with steering economic thinking away from Keynesian ideas, and who influentially argued that there are limits to what the government can do to boost employment — recommended a very similar course of action to that being promoted by Smith and others. At about the same time, Bernanke — then a Federal Reserve governor — publicly urged Japan’s central bank to set an explicit inflation target of 3 to 4 percent, so that it might bring prices back to the long-term trend.

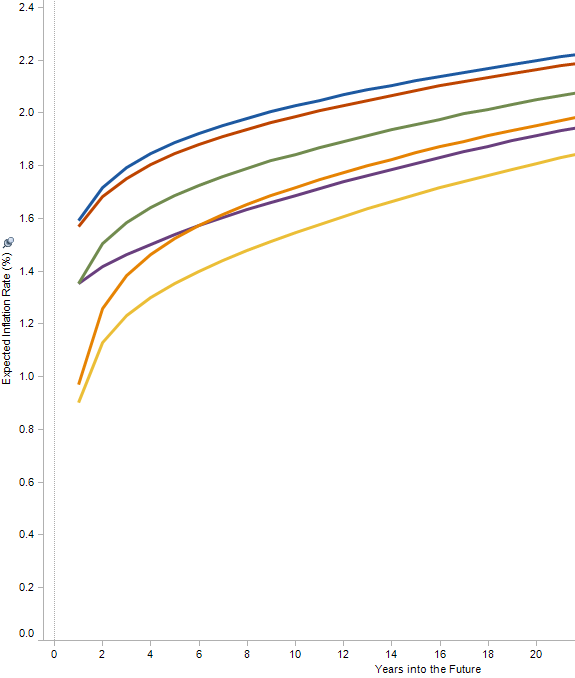

Today, in his role as Fed chairman, Bernanke acknowledges that inflation has fallen too low, but he rejects calls for aggressive action. His argument rests in part on the claim that expectations about future inflation — which influence the current demand for money and the value of assets — are “well-anchored” (that is, stable). Data collected by the bank’s Cleveland branch, though, show that is not the case: since April, as the chart titled “Recent Inflation Rate Expectations” shows, expectations about future inflation have fallen consistently.

Elsewhere Bernanke has worried, as he did in Jackson Hole, that boosting inflation could cost the Fed credibility — that, in essence, the public will lose confidence in the bank’s inflation-fighting bona fides, and we will relive the experience of the 1970s. Sumner argues that this concern is ill-founded, because of technical and analytical advances in the ability to detect and correct any nascent hyper-inflationary trends. Even if there is some risk, Ball added, “that doesn’t seem a big enough worry relative to the certainty of the terrible human cost of unemployment staying at 10 percent.”

Why the Bernanke Fed has not followed the logic of Bernanke’s earlier insights — and why the particular lessons of the 1970s and early 1980s loom so much larger in its thinking than other concerns — remains a puzzle. It may be explained in part by an internal disagreement about whether the rise in unemployment is really driven primarily by a massive failure of demand, or by other, “structural” factors.

The term “structural unemployment” has gone in and out of vogue over the years, its precise meaning shifting with each intellectual cycle. In the current debate, it refers to what’s also known as “mismatch” — the idea that businesses actually do want to hire employees but can’t find any quality candidates, because too many workers have skills that are only useful to industries in which there is little demand (like housing construction), or are trapped in regions far away from the jobs (like Florida). The core piece of evidence for this claim, called the Beveridge curve, shows the correlation between job vacancies and unemployed workers. The relationship has generally been steady, but beginning in 2009 the numbers diverged, with the unemployment rate well above what the curve would predict.

The argument is significant because, if unemployment of nearly 10 percent is caused by “structural” factors — either a temporary mismatch between jobs and workers, or, as some critics worry, a long-term degradation in the skills of the American workforce — there’s not much that the Fed can do about it. “Most of the existing unemployment represents mismatch that is not readily amenable to monetary policy,” Narayana Kocherlakota, the president of the Minneapolis branch of the Federal Reserve, told an audience in Michigan in August, because “the Fed does not have a means to transform construction workers into manufacturing workers.” Other regional Fed presidents have offered different reasons for the bank to stand pat: that sluggish hiring and business investment is actually a result of regulatory uncertainty, or that by adjusting its policy to meet political demands, or pick up the slack for Congress, the Fed would compromise its independence. But the structural unemployment argument is the most direct challenge to the case for central bank action: the Fed can pump all the money it wants into the economy, but if American workers can’t produce the things that consumers want to buy, that money can’t be spent in ways that create jobs.

But while there are probably elements of truth to the structural story, it cannot explain why unemployment abruptly spiked. For one thing, Kocherlakota’s estimates for the consequences of “mismatch” — he put the impact at about 2.5 percentage points of unemployment, or nearly 4 million out-of-work individuals — are likely too high. Kocherlakota cited as support for his argument the research of a University of Chicago economist named Robert Shimer, but in a recent interview, Shimer described skill mismatch as a long-term process, not a sudden shift. Kocherlakota’s hypothesis was “reasonable,” Shimer said, but he added, “I don’t know of any evidence that [skill mismatch] is really going on at a greater rate than the process of structural change which has been happening since the Industrial Revolution.” Geographic mismatch, meanwhile, might be a factor — but since only about 1 percent of homeowners move for job-related reasons in a given year, that can account for at best a small fraction of the increase in joblessness.

Critics of the “structural” argument have also noted that employment is down across almost all industries, and that, until recently, joblessness was trending up even for college graduates — both symptoms of widespread economic dysfunction, not labor market mismatch. And researchers at the Cleveland Fed recently concluded that the “natural rate” of unemployment — a term coined by Friedman to describe the level of joblessness he believed was built into the economy at a given time — has risen only slightly, to about 5.6 percent; the dramatic increase, they found, is “largely a cyclical phenomenon.”

Even accepting Kocherlakota’s analysis, though, structural factors — in addition to “mismatch,” these include the extension of unemployment benefits, which are believed to modestly push up the jobless rate — can’t explain the whole story. He has estimated that these factors cumulatively account for about 3 percentage points of unemployment, but from April 2008 to August 2010, the rate rose from 5.0 to 9.6 percent. A broader measure of hiring stress — the U-6 rate, which includes workers who are employed part-time for economic reasons, or “marginally attached” to the labor market — also nearly doubled, to more than 17 percent. Thus, even if you believe structural factors that the Fed can’t do anything about are playing a role — as Kennedy did in 1960, when he worried about those mine workers displaced by newer, better machines — doesn’t it make sense to try to do something to create jobs for the rest of the unemployed?

Through a spokesperson, Kocherlakota declined to address that question. Others in his orbit did comment, though. In September, I asked Randall Wright, an economist at the University of Wisconsin who serves as a consultant to the Minneapolis Fed, for his thoughts on the higher-inflation strategy. The idea was “terribly misguided, bordering on ignorant, and probably dangerous,” he replied — the economic equivalent of prescribing leeches for sick patients.

Part of the objection lies in an empirical dispute: in his academic work, Wright has argued that there is a persistent, positive long-run relationship between inflation and unemployment. “Inflation disrupts the exchange process, which is not good for business and job creation,” he wrote me. “That seems relatively obvious.”

But underlying the disagreement is also a different set of calculations about the cost of different economic ills, and a different sense of what policy can accomplish. Even if “by some miracle” inflation could reduce joblessness in the short run — “say, by confusing people into taking a job that is not right for them” — it wouldn’t be worth it, Wright said. Later, he added:

Suppose a [given] increase in inflation reduced growth by even a tiny amount. Once capitalized over several years this dramatically lowers output. Even if it reduced unemployment, this would be terrible. A [given] change in the growth rate is not equal in terms of welfare to [an equivalent] change in unemployment.

At about the same time, Wright’s co-author Stephen Williamson — an alumnus of the Minneapolis Fed who is now affiliated with the Richmond and St. Louis branches — penned a lengthy blog post in which he distanced himself from Keynesian “good-deed-doers.” He was referring to people who tend to believe that “doing nothing in a recession, when unemployment is high and real GDP is low, would be cruel as well as inefficient.” I followed up to ask: does the government have any role in trying to push back against spikes in unemployment?

It “very much depends very much on the circumstances,” Williamson replied. “One can make a case that the principle goal of the Fed should be inflation control, and that they should ignore other things (in part because, once you control inflation properly, you have exhausted the Fed’s ability to do good).” (There is, Williamson acknowledged, legislation that directs the Fed to care about unemployment, but the law is “pretty vague.”) In his initial email to me, Wright had offered a similarly circumscribed policy vision. “The first rule here should be do no harm. Please do no harm,” he wrote. “I do not mean to suggest that I know a first-best fail-safe cure for our current troubles. But I am 95 percent sure it is not leeches.”

Toward the end of our exchange, I asked Wright and Williamson: Aren’t advocates of higher inflation now calling for much the same thing that the Fed chairman urged on Japan a decade ago? If they are wrong, was he, too? Wright replied first: “Bernanke still thinks like the outdated undergraduate textbooks he learned from: he believes, sincerely I trust, that we can increase output and reduce unemployment by printing more currency.”

Outdated or not, that is in fact the logic – we are experiencing a shortfall of demand, and money is in too short supply – that Bernanke and others in the Fed have articulated. In contrast, Kocherlakota’s interpretation of the economy apparently commands only minority support within the bank. So it is hard to say for certain why the Fed’s leadership has not so far moved further away from the anti-inflation instincts that took root in the 1980s.

When Ben Bernanke offered his plan for the Japanese economy over a decade ago, he, like some of those watching him today, was baffled by the failure to act more assertively. “Policy options exist that could greatly reduce these losses. Why isn’t more happening?” Bernanke asked. “Most striking is the apparent unwillingness of the monetary authorities to experiment, to try anything that isn’t absolutely guaranteed to work.” Japan was suffering from “self-induced paralysis,” when what was needed, he said, invoking America’s experience with the Great Depression, was “Rooseveltian resolve” — a willingness “to be aggressive and to experiment,” in the conviction that a solution could be found, pain alleviated, idle resources put to work.

That determination to act when necessary, along with his stellar reputation within the profession, seemed to make Bernanke well suited to lead the Fed during the current crisis. UNC’S Smith, for one, had been willing to be patient. “There was a long while where it felt like, eventually they’re going to tell us” what the plan is. “Maybe there’s an enormous amount going on behind the scenes,” he recalled. But “then it keeps not happening, and it keeps not happening, and there’s a point at which you break — you just break.”

For Smith, that point might have come in early September. Bernanke had recently given his speech in Jackson Hole; a few days later, a new round of unemployment numbers was released, showing the jobless rate steady at 9.6 percent and more than six million people out of work for six months or more. With much of the debate about the economy dominated by political talking points, or by the idea that the recession’s pain represented some necessary sacrifice, Smith sounded a stark warning: “Rome,” he wrote, “is burning.”

The economy has gotten no stronger since then. But there have recently been signs that the debate is moving in the other direction. The 4% Club has added some new members. So has the Fed — in late September, the Senate approved two of President Obama’s nominees to the bank’s board of governors. Those new members of the central bank’s leadership may shift the internal debate. And there are increasing indications that the bank may take some action to increase the money supply at its next meeting in early November, although it will likely follow, The Wall Street Journal reported, a “baby-step approach.”

The most significant developments have come within the last two weeks, as two top Fed officials — William Dudley, head of the New York branch, and Charles Evans, president of the Chicago branch — have floated the possibility of an explicit, higher inflation target, at least in the short term. A Fed strategy keeping track of “inflation shortfalls” — and announcing that it plans to make up ground in the future — “would have some advantages,” Dudley said in a recent speech.

Given these shifts, some inflation advocates still hold out hope that the Fed’s instincts will yield to policy built to meet 2010 circumstances. Smith, at a loss just a month ago, is now guardedly optimistic. “It looks like we are winning this war,” he said late last week.

Nevertheless, the question of how much influence the Fed’s anti-inflation instincts will continue to exert remains open. In his conversation with me, Ball had first outlined his fear that we will be stuck with 10 percent unemployment for a decade or more. Then, he quoted Bernanke’s phrase from memory: “It’d be nice,” he said, “if they could put aside their concern about inflation sufficiently to have Rooseveltian resolve in dealing with the recession.”