Being a citizen, Danish style

Transparency and trust

Peter Abrahamson is a professor of sociology at the University of Copenhagen, who has long studied Danish institutions and policies and their impact on what it means to be a citizen. According to him, one of the central factors that has allowed the Danish democracy to function so well is that a very high level of trust exists among Danes — not only trust of the government, but also of social institutions like unions, private businesses, and of other Danes.

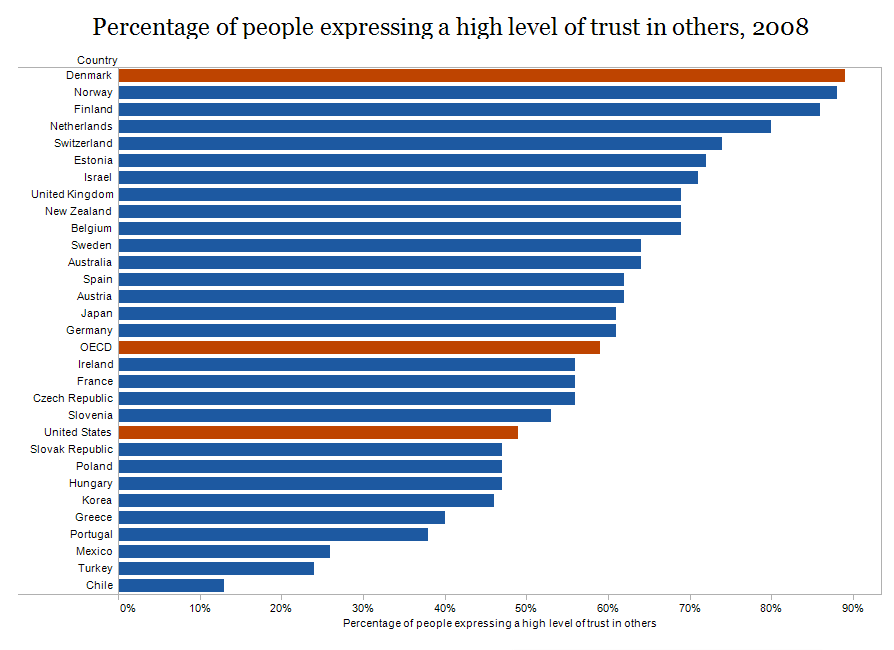

percentage of people “trusting others” in different oecd countries

Map & Data Resources

Percentage of people expressing a high level of trust in others, 2008.

“Social trust” is measured by several international organizations. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) produces a survey every year in which it asks citizens of different countries the question, “Generally speaking would you say that most people can be trusted or that you’ll need to be very careful in dealing with people?” Last year, Denmark registered the highest percentage of people who responded that they had a high level of trust in others, at 88.8 percent. The average of OECD countries was 59 percent, and in the United States, only 48.7 percent of respondents expressed a high level of trust (see chart).

Transparency International conducts a similar annual survey among countries called the “Corruption Perception Index,” where respondents are asked how much trust they have in government. Denmark has been ranked highly on this survey as well, tying two other countries for first place in 2010. “When you have such high levels of trust, that leads to greater participation and a stronger feeling of collectiveness,” Abrahamson said.

According to Abrahamson, a major reason that Danes are so trusting is that they have set up institutions that facilitate that trust, leading a virtuous, self-reinforcing cycle similar to the one that links the welfare state and the civic education system.

“People would not be so willing to pay so much in taxes if they thought that others were somehow cheating the system,” he said. “So we set up institutions that are very transparent and very hard to cheat. When no one cheats, it becomes more socially unacceptable to cheat.” The Danish tax authority, for example, frequently audits employers, Abrahamson said, reducing the likelihood of tax evasion.

And because trustworthiness is such a strong social value, Danes expect their politicians and public institutions to maintain a high degree of honesty and transparency, as well. Goul Andersen noted that in the recent campaign, a Danish politician had cited some statistics about poverty and inequality that proved to be misleading. “He had used a different measure to calculate them than the one that is usually used,” he said. “There was a very strong public reaction to that, and it was in all of the big papers.”

In that way, social trust had become a mutually reinforcing aspect of Danish society, Goul Andersen said. “We have been able to maintain this very high level of trust because we have incorporated it into our institutions,” he said.

Another crucial factor in maintaining high levels of trust is that Danes are not very open to manipulation by the government, Goul Andersen said. “[Danes] are relatively knowledgeable about how things work and are supposed to work,” he said.

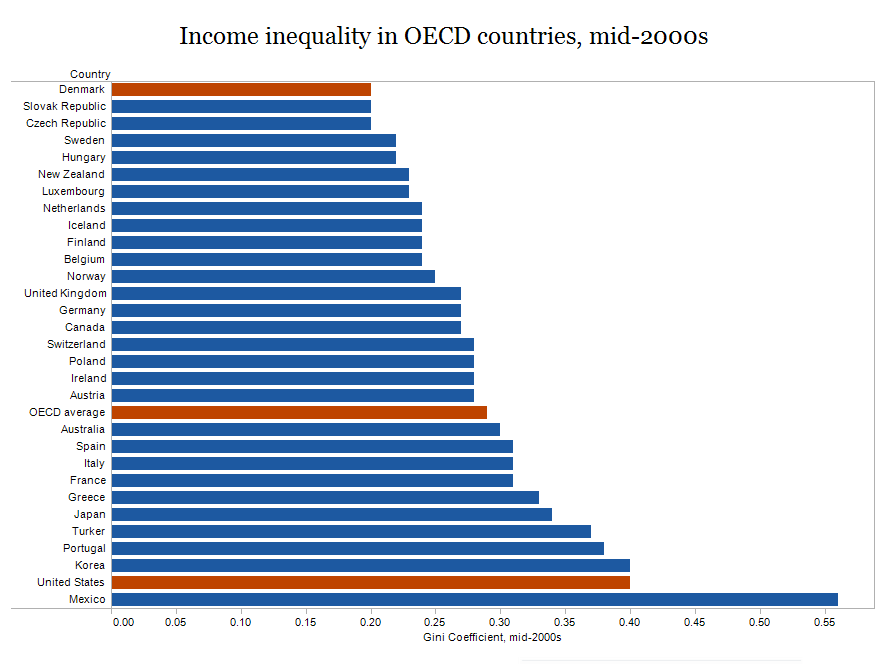

Equality

The Danish system of progressive taxation and redistribution has created one of the most equal societies in the world. Income inequality is typically quantified using a system called the “Gini Index,” a statistical tool that measures the proportion of total wealth that is owned by various percentiles of a country’s population; the lower a country scores on that index, which usually runs on a scale from zero to one, the more broadly shared its wealth. Denmark’s Gini “coefficient” was 0.20 in the mid-2000s, according to the OECD, placing it in a three-way tie for the most equal country in the OECD. The OECD average was 0.29, while the United States, at 0.40, was second to last behind Mexico among OECD countries (see chart).

Income inequality in different oecd countries

Map & Data Resources

Income inequality calculated by Gini Index, mid-2000s.

And this equality has also become integrated into Danish institutions. Per Jørgensen, the college student, named equality as the primary Danish virtue. “Most Danes would say that it is harmful for society to be very unequal,” he said. “I think that is something that Danes have in common.”

Goul Andersen described how Denmark has been able to maintain a high degree of equality even as most countries have grown more unequal in the last generation. “It is, again, a virtuous cycle,” he said. “Social equality leads to political equality, which leads to political decisions that reinforce that equality.”

Because large degrees of inequality do not exist in Denmark, there is a far lesser degree of difference between the general electorate and the officials who represent them in government.

Niels Buhl, who owns a small store in Copenhagen, said that he had only missed voting in one election in his life, and that was while he studied abroad in Germany. “My parents always told me that it is important to vote,” he said. When asked whether he felt that there was a big divide between himself and the politicians he votes for, Buhl pointed to the street outside, a busy thoroughfare that runs toward the seat of the Danish Parliament. “Sometimes you see them bicycle by here in the morning,” he said.