November 16, 2010 — The co-chairs of a bipartisan deficit reduction commission appointed by President Obama have released a proposal that calls for balancing the federal budget by squeezing health care costs, slashing military and other spending, and raising the age at which most workers become eligible for full Social Security benefits. The plan also contemplates eliminating or scaling back popular tax breaks.

All told, the report calls for more than $3.8 trillion in deficit reduction by 2020, with most of the savings coming from spending cuts. The plan asserts that it would reduce the deficit to $400 billion by 2015 — well below a target set by Obama — and close the deficit entirely by 2037.

But the plan does more than set out strategies for balancing the budget: it also proposes long-term limits on government spending and revenues as a share of the economy. That aspect of the plan — a determination about the appropriate size of the federal government — likely shaped its specific recommendations and, according to some critics, went beyond the commission’s budget-balancing mandate.

The draft proposal reflects the thinking of Alan Simpson, a former Republican senator from Wyoming, and Erskine Bowles, a chief of staff in the Clinton White House, who were appointed by Obama to lead the commission.

Fourteen of the panel’s eighteen members must agree on a proposal before the commission presents its final report to Congress on Dec. 1, and initial responses suggested the Simpson-Bowles plan may struggle to find that level of support. While independent budget hawks praised the report — Maya MacGuineas of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget called it “a remarkable plan” — many elected officials were wary. Rep. Jan Schakowsky (D-Ill.), perhaps the most liberal member of the commission, declared, “any proposal to cut Social Security or Medicare is a non-starter.” Three Republicans on the panel, meanwhile, issued a joint statement in which they praised the co-chairs’ effort but said, “we have concerns with some of their specifics.”

The proposal contains elements sure to anger different constituencies: reductions to Medicaid likely to be opposed by liberals, an increase in the gas tax that has long been fought by conservatives, and cuts to agriculture subsidies that would draw the ire of farmers. In a move that homeowners are likely to oppose, two of the three tax reform programs contemplated in the plan would cut or reduce the mortgage interest deduction.

The plan also calls for sharply curbing the long-term growth in federal health care spending, a goal that could require radical changes beyond the measures detailed in the report. Those measures include cutting payments to doctors, requiring veterans to pay more of their own medical expenses, and giving more power to a new board set up to contain Medicare costs.

But the overall shape of the plan — in particular, its emphasis on spending cuts over revenue increases — appears to have been determined by the co-chairs’ recommendation that federal spending eventually settle in at 21 percent of GDP, with tax revenues capped “at or below” that level.

In their proposal, Bowles and Simpson write that the spending target is rooted in a “guiding principle” to “cut spending we simply can’t afford.” A spokesperson for the commission did not respond to an inquiry about how the co-chairs arrived at the 21 percent figure.

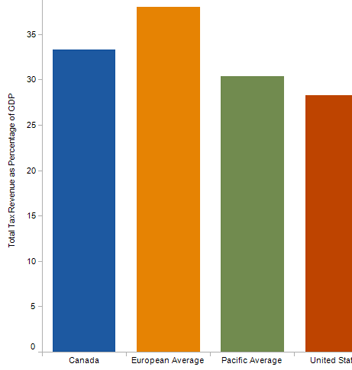

The plan would set federal revenues as a share of the economy about where they peaked in 2000, during a string of budget surpluses at the end of the Clinton administration, while leaving total government revenues in the U.S. well below those of most other developed countries. (See related chart titled “Total Tax Revenues as Share of Economy in Developed Nations.”)

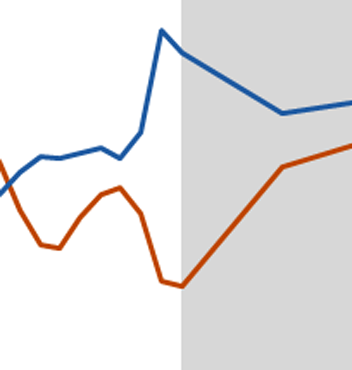

On the spending side, the 21 percent target would fall in the mid-range of recent U.S history: higher spending as a share of the economy than during Bill Clinton’s second term and the George W. Bush administration, but lower than during the presidencies of Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush. (See related chart on next page titled “U.S. Government Revenues and Expenditures as Share of Economy.”)

But while the proposed spending target is not outside the historical norm in the U.S., balancing the budget at that level would require cuts to many government programs. That is because major entitlement programs like Social Security and Medicare now account for a larger, and still growing, share of the economy, even under the cost-control provisions of the recent health care reform law and the additional changes proposed by Simpson and Bowles.

As a result, by 2020, the co-chairs’ proposed cuts to discretionary programs account for 38 percent of the progress toward balancing the budget — the biggest single factor. Their tax reform alternatives, which include a proposal to eliminate credits and deductions while lowering rates across the board, would do about half as much to close the deficit. New revenues from other sources, meanwhile, amount to less than 6 percent of the proposed deficit reduction.

The co-chairs’ 21 percent target drew a mixed response from budget-watchers. Chris Edwards of the libertarian Cato Institute called it an “interesting” approach, and said the overall proposal would move the country “part of the way” toward his group’s vision of smaller government. He suggested converting Medicare to a voucher program, introducing private accounts for Social Security, and making deeper cuts to discretionary spending as ways to advance that effort further.

“The cuts they have are good, but they don’t go far enough,” Edwards said, adding that federal cuts were an “opportunity” to shift responsibility to state and local governments and the private sector.

Other observers agreed that setting limits on the size of the government would require far-reaching changes, but warned the consequences would be negative.

The key factor driving future growth in government spending is escalating health care costs; even the aggressive cost-control targets in the proposal anticipate that health care expenses will continue to grow faster than the economy. Paired with a cap on overall spending, that trend will squeeze out other programs, said Andrew Fieldhouse, a budget analyst for the left-leaning, non-partisan Economic Policy Institute.

“Short of taking the hatchet to Medicare, I don’t think you can realistically expect to hold federal spending to 21 percent of GDP without placing severe constraints on the military, on education, [or other] national priorities,” he said. “All you’re going to do is gradually hack away at the discretionary budget.”

Both Fieldhouse and Michael Linden of the Center for American Progress, another left-leaning organization, criticized the commission’s decision to set any figure for the overall size of the government as “arbitrary.” “That is not the right way to do public budgeting. You don’t start with your bottom line,” Linden said. “What we really need to do is decide what do we want the federal government to do, and how do we pay for it.”

The 21 percent figure may have been selected in an attempt to win political support, Linden said, because it is close to the level of revenue the government collected the last time the budget was balanced. But “whatever we had in the past is not a particularly good guide for what we’re going to need in the future,” he said.

Brad DeLong, a University of California economist, outlined another direction the co-chairs might have taken. He pointed to Congressional Budget Office estimates showing that under certain scenarios, the long-run deficit could actually wind up being far smaller than is commonly assumed — less than 1 percent of GDP over the next 50 years. That projection assumes that Congress would allow the Bush tax cuts to expire as scheduled at the end of this year, and would not annually adjust the alternative minimum tax (AMT) for inflation — two courses of action that now seem politically unlikely.

Alternative CBO projections based on steps Congress is more likely to take, such as extending the tax cuts and indexing the AMT, show much larger deficits. But by leaving current law in place and then taking a few other steps — such as raising Social Security taxes on top earners, introducing a small carbon tax, trimming civilian and defense spending, and ensuring that new programs or tax cuts are paid for — Congress could balance the long-run budget even without further entitlement cuts, DeLong said.

But such a strategy would also leave federal spending at about 24 percent of GDP over the next half-century, the type of approach that would be rejected out of hand under the Bowles-Simpson guidelines.