Selling defined contribution health plans: benefit-cutting vouchers in “employee choice” clothes

If the companies do not increase their contribution by at least as much as the rise in insurance costs, the employer’s contribution will pay for less and less of the costs of insurance premiums, which will mean that, to buy the same level of coverage, workers will have to pay an increasing amount out of their own pockets.

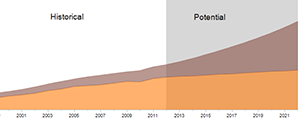

a growing gap

Map & Data Resources

As employers’ contributions shrink, employees’s share of insurance costs will grow.

“The first year out, they might hold employees basically harmless from the prior year, so they can tell employees that they won’t pay any more out of pocket than they did last year,” said Kathleen Stoll of Families USA. “But over time it’s a sure bet that the size of the defined contribution won’t grow as fast as premiums.”

Mark Dudzic, a longtime union leader and the national coordinator of the Labor Campaign for Single Payer, agreed. Even if companies do increase their contribution at the overall rate of inflation, he said, workers will lose.

“Let’s say they’re currently paying $10,000 per employee for health care coverage,” he said. “If the CPI” — the Consumer Price Index, or the most common measure of overall inflation — “goes up two percent a year, and healthcare costs go up five percent a year, then next year [the company is] going to give $10,200 and the plan will cost $10,500. And the year after that, and the year after that…so you’re going to see those growing spreads.” Using the same calculation and assuming the same numbers, after ten years the gap between the contribution and the cost of insurance would be more than $4,000 (see sidebar titled “A growing gap”).

But because the increase in costs borne by the employee will be gradual, the employees might not become immediately aware of it, said Balber of Consumer Watchdog.

“Decreasing the contribution over time is much less visible than simply dropping coverage, so people may not immediately be as worried,” she said.

Alternatively, if the cost of coverage is rising faster than the employer’s contribution, the employee may feel forced to sign up for an insurance policy that costs the same amount but which offers less robust coverage.

“If the employer has a fixed amount of money to work with that is not increasing as fast as the cost of insurance, then we would expect that to lead to an erosion in coverage over time,” said Leonard Fleck, a professor of philosophy and medical ethics at Michigan State University.

For example, Fleck said, employees might opt for a plan with a lower premium and a higher deductible, meaning that they will pay more out-of-pocket for any care they receive. “So then if you get sick or you fall down the stairs and break your hip, you could quickly rack up a lot of medical bills,” he said.

While the Affordable Care Act does provide some protections in terms of what benefits an employer must offer and how much an employee can be forced to pay, many of those regulations have not been fully written, and patient advocates see risks that many of those provisions may not adequately protect workers (click here for our detailed explanation).

Adverse selection

According to Stoll, there is another way that a shift to defined contribution plans might push high-quality coverage increasingly out of the reach of workers, through a process known as “adverse selection.”

Adverse selection occurs if young or healthy workers, knowing that their risk of serious illness is relatively low, gravitate to lower-cost plans that provide only basic minimal coverage. As the minimal coverage plan covers more and more lower-risk workers, the insurer’s overall risk for that plan is lessened, and premiums might be reduced further over time.

Meanwhile, older and sicker workers, who anticipate needing more medical care, may gravitate to plans that provide for more and better coverage. The insurer will then see the more comprehensive plan as insuring a riskier pool of workers, giving the insurer an incentive to raise costs on the comprehensive plan still further.

“So people who are older or expect for some reason to have some medical expenses, exactly the people that we want to have the most access to insurance, are going to have an even harder time getting it than they were before,” Stoll said.

Several experts pointed out that benefits have already been significantly eroded in the group insurance market, as many employers have switched to “consumer-directed” health care models in which low premiums are coupled with very high deductibles and occasionally a health savings account. But Stoll of Families USA said that the implementation of the fixed contribution model could greatly exacerbate that problem. When their contribution to health insurance is already limited to a fixed amount, Stoll said, employers will be more liable to make changes to that contribution. If the company has a bad year, for example, it may simply choose to freeze the contribution or even lower it in order to cut costs.

“It has the potential to become a dial that’s very easy to turn,” Stoll said.

Additionally, there is no guarantee that, over time, the plans available to workers in the exchange will not themselves erode. If larger and larger numbers of workers are pushed into lower-quality plans because the higher quality plans are not affordable, Fleck explained, then higher quality plans may be eliminated for lack of demand. If that happens, then what is currently considered a “bronze” level of coverage might eventually be re-labeled as a “gold” level of coverage.

“Really high-quality coverage could become out of reach” for the ordinary worker, Fleck said.

When asked whether Darden was providing any guarantee to workers that the coverage available to them through the exchange would not erode over time, Ron DeFeo, a spokesperson for the company, said only, “We’re taking this one year at a time.”