The Deficit Commission's 21-percent solution

The co-chairs’ 21 percent target drew a mixed response from budget-watchers. Chris Edwards of the libertarian Cato Institute called it an “interesting” approach, and said the overall proposal would move the country “part of the way” toward his group’s vision of smaller government. He suggested converting Medicare to a voucher program, introducing private accounts for Social Security, and making deeper cuts to discretionary spending as ways to advance that effort further.

“The cuts they have are good, but they don’t go far enough,” Edwards said, adding that federal cuts were an “opportunity” to shift responsibility to state and local governments and the private sector.

Other observers agreed that setting limits on the size of the government would require far-reaching changes, but warned the consequences would be negative.

The key factor driving future growth in government spending is escalating health care costs; even the aggressive cost-control targets in the proposal anticipate that health care expenses will continue to grow faster than the economy. Paired with a cap on overall spending, that trend will squeeze out other programs, said Andrew Fieldhouse, a budget analyst for the left-leaning, non-partisan Economic Policy Institute.

“Short of taking the hatchet to Medicare, I don’t think you can realistically expect to hold federal spending to 21 percent of GDP without placing severe constraints on the military, on education, [or other] national priorities,” he said. “All you’re going to do is gradually hack away at the discretionary budget.”

Both Fieldhouse and Michael Linden of the Center for American Progress, another left-leaning organization, criticized the commission’s decision to set any figure for the overall size of the government as “arbitrary.” “That is not the right way to do public budgeting. You don’t start with your bottom line,” Linden said. “What we really need to do is decide what do we want the federal government to do, and how do we pay for it.”

The 21 percent figure may have been selected in an attempt to win political support, Linden said, because it is close to the level of revenue the government collected the last time the budget was balanced. But “whatever we had in the past is not a particularly good guide for what we’re going to need in the future,” he said.

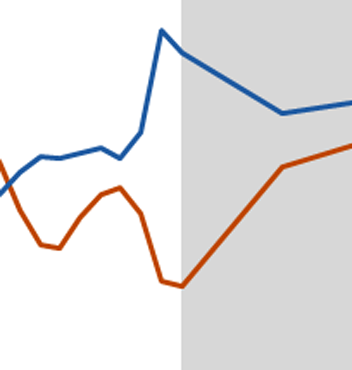

Brad DeLong, a University of California economist, outlined another direction the co-chairs might have taken. He pointed to Congressional Budget Office estimates showing that under certain scenarios, the long-run deficit could actually wind up being far smaller than is commonly assumed — less than 1 percent of GDP over the next 50 years. That projection assumes that Congress would allow the Bush tax cuts to expire as scheduled at the end of this year, and would not annually adjust the alternative minimum tax (AMT) for inflation — two courses of action that now seem politically unlikely.

Alternative CBO projections based on steps Congress is more likely to take, such as extending the tax cuts and indexing the AMT, show much larger deficits. But by leaving current law in place and then taking a few other steps — such as raising Social Security taxes on top earners, introducing a small carbon tax, trimming civilian and defense spending, and ensuring that new programs or tax cuts are paid for — Congress could balance the long-run budget even without further entitlement cuts, DeLong said.

But such a strategy would also leave federal spending at about 24 percent of GDP over the next half-century, the type of approach that would be rejected out of hand under the Bowles-Simpson guidelines.